4 May 2024

As I mentioned on Thursday morning, I spent a few days this week at Magee Marsh boardwalk where I experienced the quiet days before The Biggest Week in American Birding. On Thursday 2 May the weather was great, there were more birds to see, and there were 5 times as many people compared to Tuesday. That’s when I re-learned the advantages of birding with a (small) crowd.

I happened to be on a quiet section of the boardwalk when I noticed a crowd forming ahead. Many people were focusing binoculars and cameras at the spot where two guides were pointing and explaining a bird. I rushed over to find out what was up.

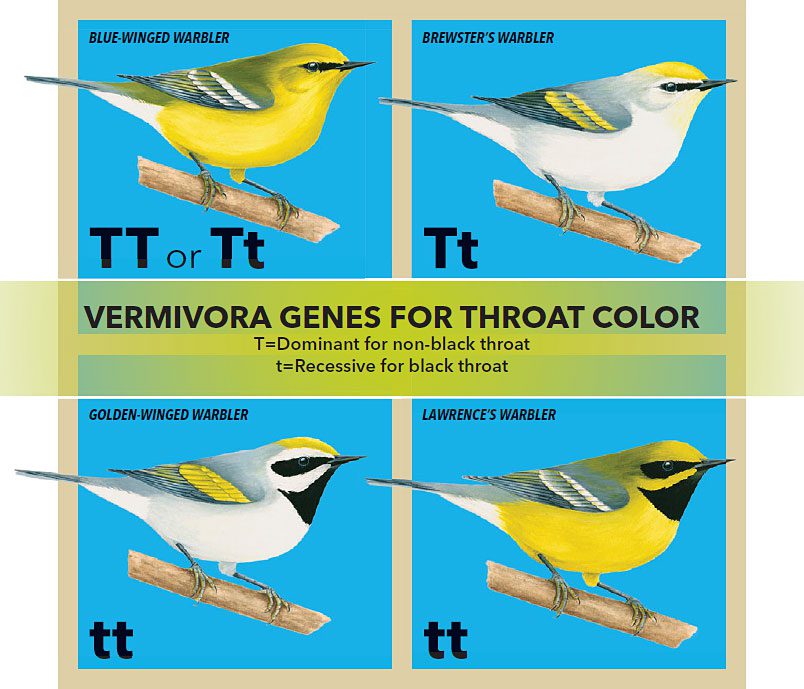

On my first look at the bird, I thought “golden-winged warbler” because of its yellow wing, yellow crown, and whitish chest (see example at top), but something wasn’t quite right. Word was spreading through the crowd that this was a Brewster’s warbler, the hybrid offspring of golden-winged x blue-winged warblers. Though not technically a species, for me it was a Life Bird.

The big difference between a Brewster’s and a golden-winged is that the Brewster’s looks pale with a white throat (not black) and a black eyeline (not a wider face patch). Here’s a side-by-side comparison of a male golden-winged warbler vs. a Brewster’s warbler.

This diagram embedded from Cornell Lab’s All About Birds shows the warbler’s parents on the left and the Brewster’s in the top right corner. The parents can also produce another variation: a Lawrence’s warbler (bottom right) which I have never seen. Click on the caption to read about their genetics.

I left Magee Marsh yesterday morning while it was raining steadily so I missed the Brewster’s reappearance but my friend Kathy Saunders saw him on 3 May in the same place as the day before.

Yay! Best Bird!

(credits are in the captions)