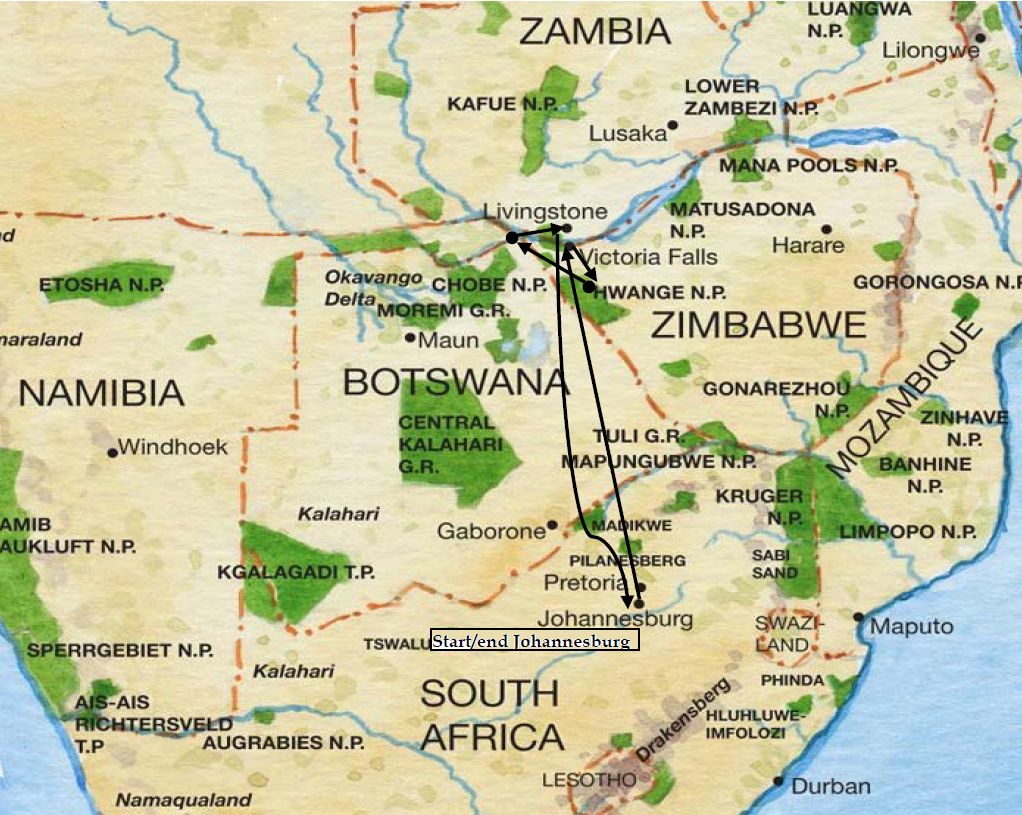

27 January 2024: Day 9, Chobe National Park, Botswana — Road Scholar Southern Africa Birding Safari. Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

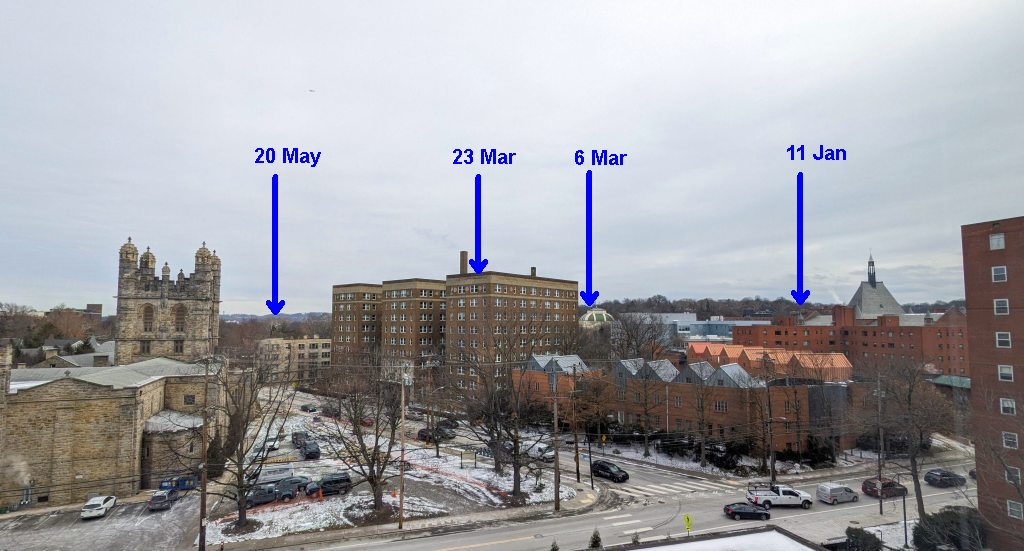

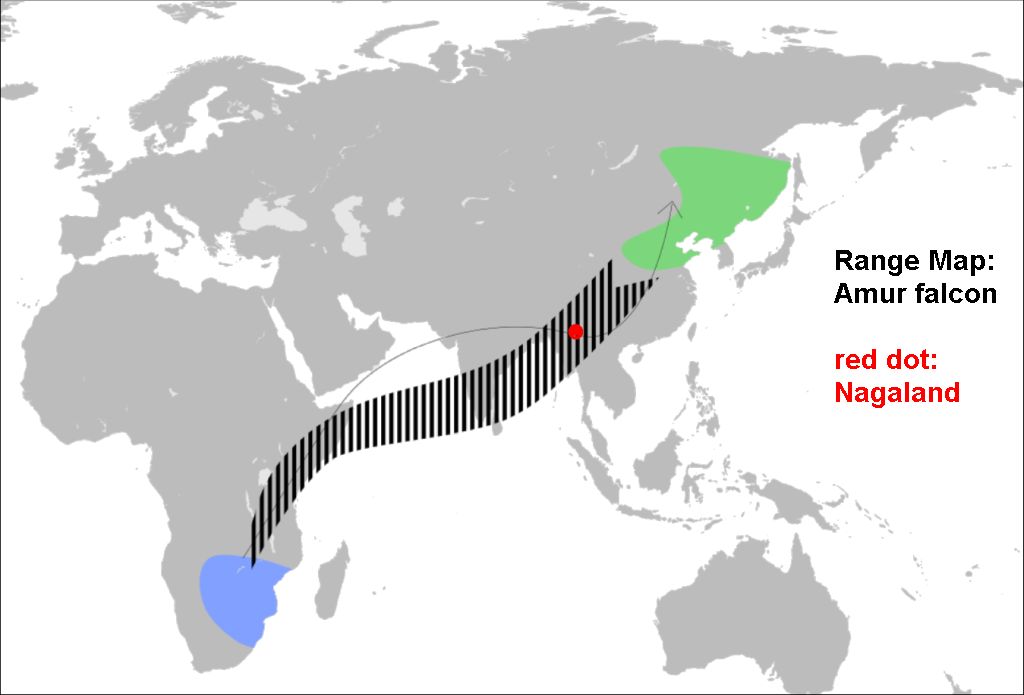

Amur falcons (Falco amurensis) breed in Siberia and northern China and travel 22,000 km (13,670 mi) each fall to southern Africa. Not only is their migration the longest of all the raptors but when they stopover in autumn to refuel in Nagaland, India their flock can number half a million birds. Right now they’re in southern Africa where I hope to see them.

Amur falcons are insectivores who, on migration, capture flying insects to eat in mid air.

They time their migration and choose a route to take advantage of insect swarms.

- In northeastern India winged adult termites swarm in autumn in Nagaland.

- Over the Arabian Sea dragonflies migrate in the fall from India to Africa.

- In southern Africa, December to March rains spawn swarms of termites, locusts, ants and beetles.

Amur falcons are present from October to December near the Nagaland village of Pangti where they fatten up on termites before continuing their journey. There are hundreds of thousands of falcons in the air at once.

Their abundance led to near tragedy, however. Until the practice ended in 2012, Nagaland hunters caught tens of thousands of falcons per day in fishing nets hung from the trees. Each year they killed 250,000 Amur falcons to sell as meat for mere pennies. They thought the falcons would never disappear.

The killing ended abruptly when journalist Bano Haralu returned to her homeland, witnessed the destruction, and got a hunting ban placed in November 2012. More importantly, she and her colleagues taught the villagers, and especially the children, the importance of the falcons and a way forward through ecotourism. It was a stunning turnaround and a credit to the people of Nagaland.

In 2018 Scott Weidensaul went to Pangti to see the birds and tell their amazing story in A Galaxy Of Falcons: Witnessing The Amur Falcon’s Massive Migration Flocks. Birders flocked to the spectacle last fall.

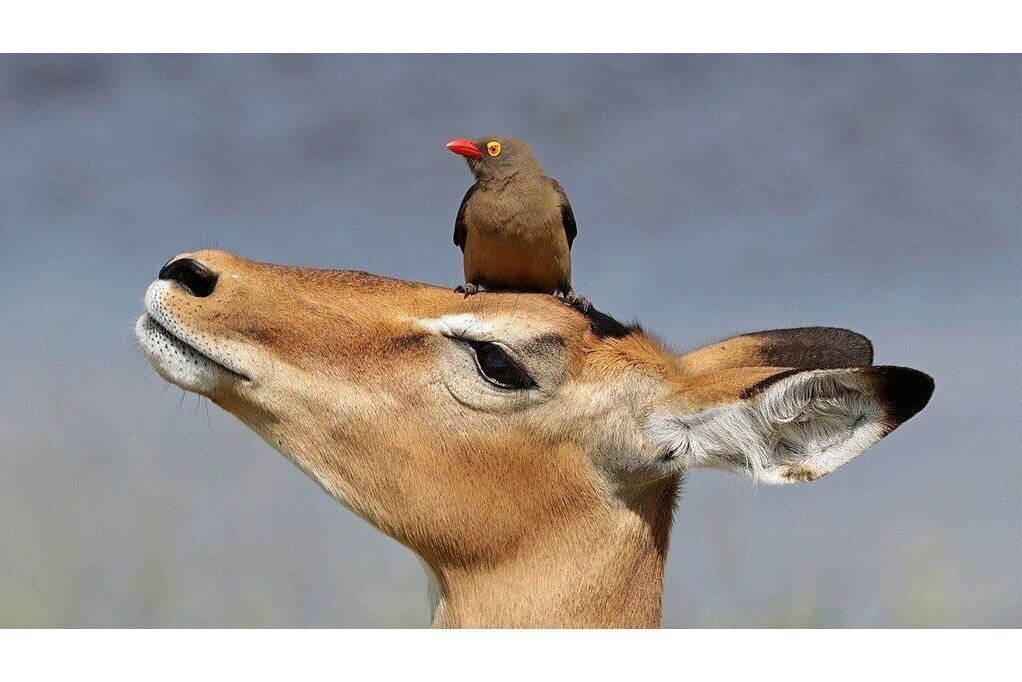

UPDATE on 29 January 2024: I was fortunate to see a female Amur falcon in Namibia today, swooping for insects near the Chobe River. (These photos are from Wikimedia.)

For more information see:

- The Pangti Story: How a Nagaland village turned from hunting ground to safe haven for Amur falcon.

- Bano Haralu’s journey, The Lady Who Saved the Falcon. Haralu’s work continues at the Nagaland Conservation and Livelihoods Team of WCS-India.