17 March 2024

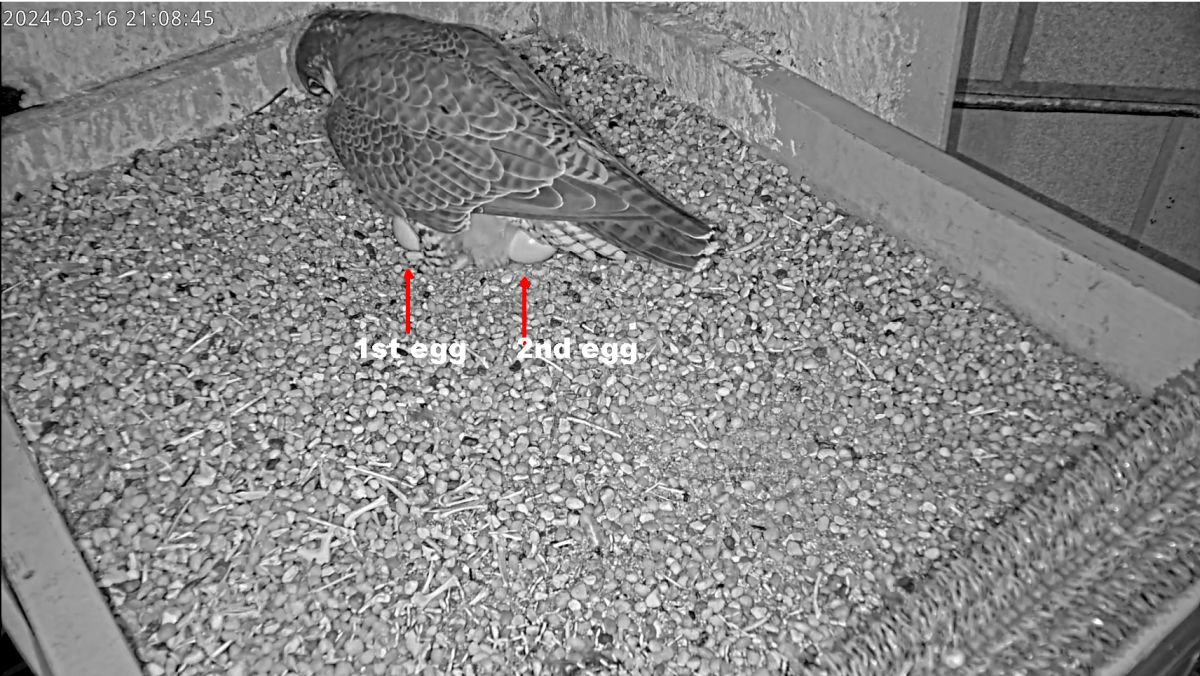

Carla laid her second egg last night at the Pitt peregrine nest, 16 March 2024 at 9:08pm.

In this video clip from the National Aviary falconcam we see the actual laying occurred quietly at timestamp 21:08:38. (This is 53.14 hours after her previous egg.)

Carla then raised her tail and remained in a standing position as she waited for the new egg to dry. Though the eggs are actually reddish in daylight, they look white under infrared night light.

After the egg dried Carla roosted on the green perch in front of the nest.

Mother peregrines are the ones who stay at the nest overnight with eggs and chicks while their mates roost nearby. Ecco was apparently roosting within earshot but not very close. I believe he knew she had laid a second egg; he probably watched (off camera) when she laid it.

Carla was still asleep on the perch when it rained at 4:00am. When Ecco woke up at 4:30am he started to wail. Wailing means “I want something to change.” Perhaps Ecco wanted Carla to cover the eggs or maybe he meant, “I want to change places with you.”

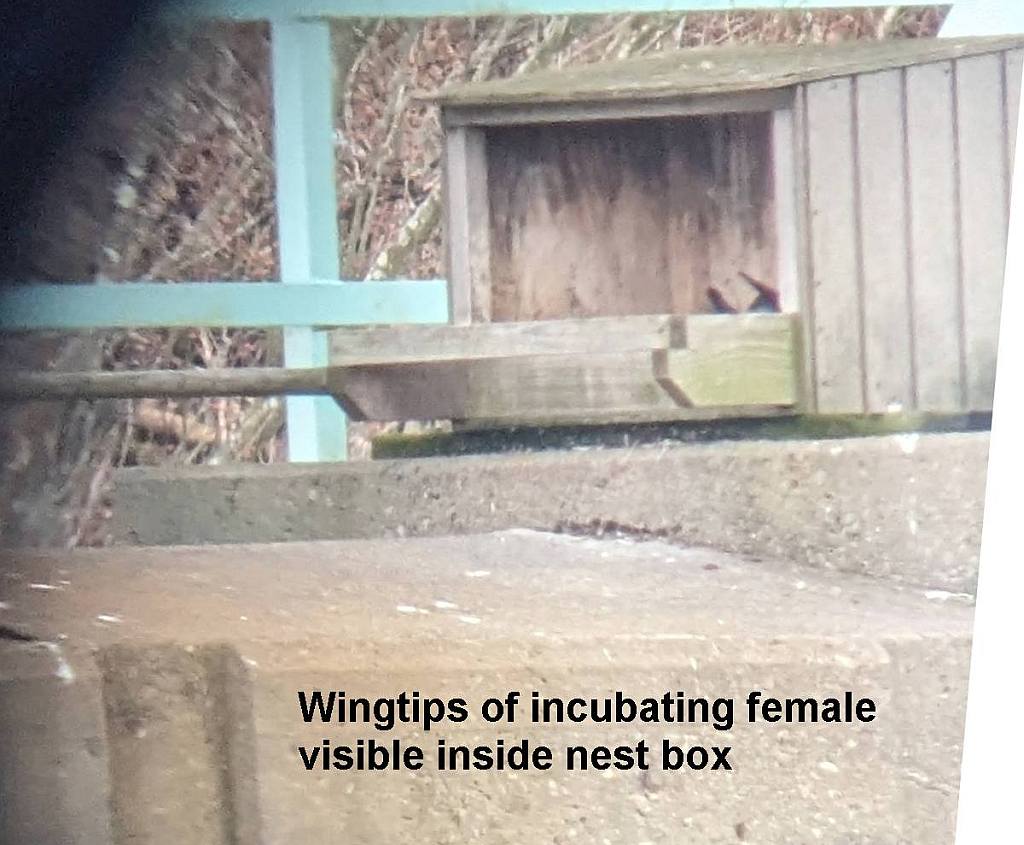

Carla woke up and responded with unusual squeaky chirps. She jumped to the nestbox roof and Ecco arrived to cover the eggs. Listen for his voice and the sound of robins singing in the dark at the beginning of this video.

An overnight nest exchange is very unusual but I’ve seen it once before. When Dori was a new mother at the Gulf Tower in 2010, Louie took over incubation in the middle of the night a couple of times (*). Louie had experience raising a family and Dori did not. Perhaps he was getting the eggs through a critical period, waiting until he felt confident that Dori had caught on.

Peregrines are quick studies at being parents but it’s always nice when one of them already knows what’s going on, as Ecco does.

Watch Carla and Ecco as their family grows at the National Aviary Falconcam at Univ of Pittsburgh.

(*)The nighttime nest exchanges at Gulf Tower in 2010 are described in these vintage blogs.

(credits are in the captions)