17 February 2024

Juncos have been a joy this month. I’ve consistently seen flocks of 10-15 in Schenley and Frick Parks.

This week an ornamental witch hazel burst into full bloom in my neighborhood.

And then it snowed.

17 February 2024

Juncos have been a joy this month. I’ve consistently seen flocks of 10-15 in Schenley and Frick Parks.

This week an ornamental witch hazel burst into full bloom in my neighborhood.

And then it snowed.

16 February 2024

Why is this magpie annoying the cat?

Magpie following a cat pretending it’s not

— Science girl (@gunsnrosesgirl3) February 14, 2024

pic.twitter.com/NftmN9Jq3b

When they aren’t viewing cats as threats to their young, Eurasian magpies (Pica pica) will follow them to sources of food.

As soon as this cat found a snack …

… the magpie showed up to wait.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, tweet embedded)

15 February 2024

Plant pollination has been declining for many reasons including the absence of insects due to pesticides and habitat loss. Now a new reason has surfaced that has nothing to do with the number of flowers and bugs. Research has found that air pollution prevents nighttime pollination by turning off the scent of flowers.

The white-lined sphinx moth (Hyles lineata) is an important nighttime pollinator of purslane, primrose and rose. The research team led by J.K.Chan in eastern Washington, teased out the chemical emitted from pale evening primrose (Oenothera pallida) that attracts the hawkmoths.

The moths were particularly tuned to two different flavors of monoterpenes, a class of chemicals found in plant oils [that] evaporate quickly in the air. Moths, whose antennae are roughly as sensitive as a dog’s nose, can pick up the scent several kilometers away from a flower.

But there is an Achilles heel. When the researchers exposed the monoterpenes to NO3, it reacted with the oils, causing them to degrade by between 67% and 84%.

— Anthropocene Magazine: Nighttime pollination is plummeting. Some clever sleuthing pinpointed a surprising culprit.

Air pollution doesn’t just change the scent of flowers. It erases the scent. The moths can’t find them.

Anthropocene Magazine continues, “While NO3 [a component of NOx] is less of a problem during the day because it breaks down in sunlight, it accumulates at night, when many pollinators, including the hawkmoths, are active.”

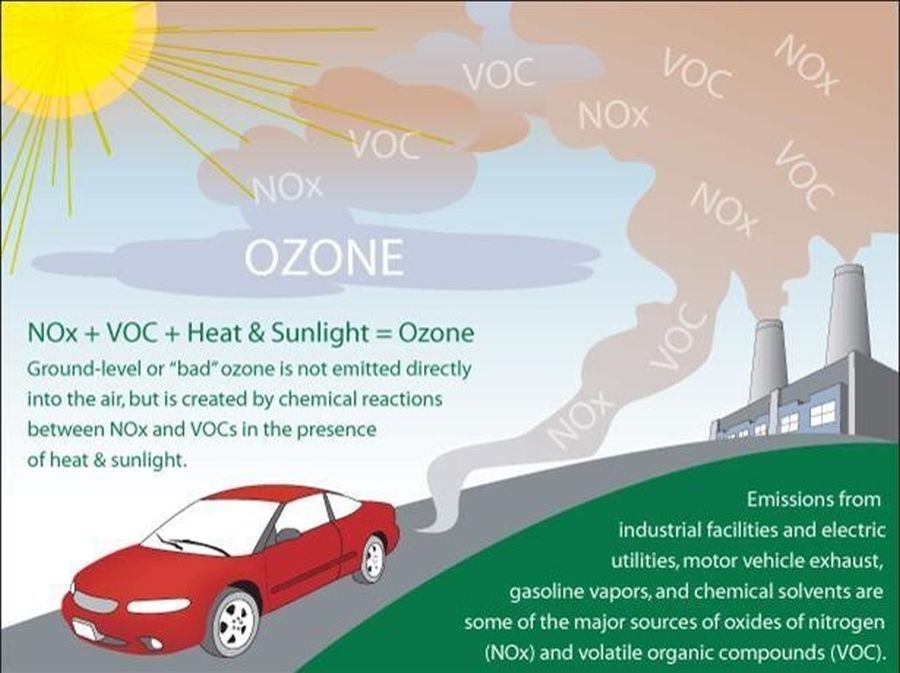

NOx causes trouble for humans, too, because it combines easily with VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds) to create ground-level ozone (the bad ozone) and fine particulate which is inhaled so deeply into our lungs (PM2.5).

If we reduce NOx pollution we help ourselves and plants at the same time.

(photos and diagram from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)

14 February 2024

Last week when I wrote that Charles Bier had seen two peregrines at Pittsburgh’s East Liberty Presbyterian Church in January, Adam Knoerzer responded that he has too.

Last week, out of my office window (which looks at the church from Friendship), I could definitely see a raptor high up and stooping to dive bomb some small birds and wondered if it might be a peregrine. I’ll keep an eye out and see if anything else is brewing.

— message from Adam KnoerZER, 7 Feb 2024

Later that day Adam checked onsite and immediately found both peregrines.

Confirmed peregrines at the church just now walking past. One darted off the ledge and flew over me and rejoined the other that was presumably eating (small feathers started to fall down).

— message from Adam KnoerZER, 7 Feb 2024

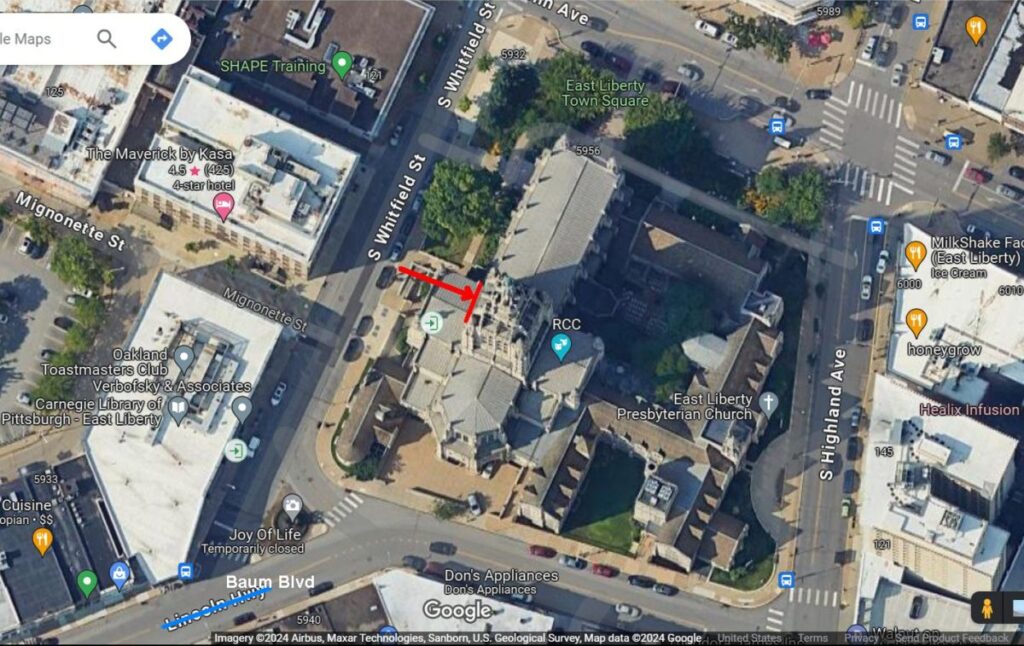

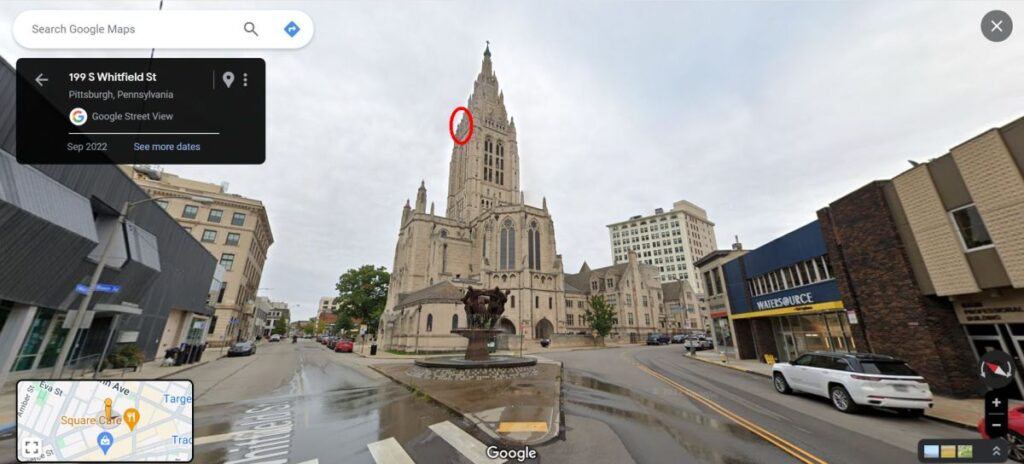

He sent photos of the church steeple with circles indicating the peregrines’ locations. Their favorite spot is behind the “railing” on the west-northwest side, a likely choice for a nest location.

On Monday 12 February Adam saw peregrines circling the steeple and perching on nearby buildings.

Today I was able to spot what appeared to be the female (larger of the two, so…) perched atop the Walnut on Highland apartment across from the church. The bird has a very distinct and prominent peach-y color at the top of the breast, and the other bird (presumably the male) flew off the tower, circled around, and found another perch high atop the cross.

— Pittsburgh Falconuts Facebook post by Adam KnoerZER, 12 Feb 2024

Thanks to Adam’s efforts we know there’s a new peregrine pair in East Liberty.

In case you would like to check on them, take a look at the steeple on the west-northwest side that faces S. Whitfield Street.

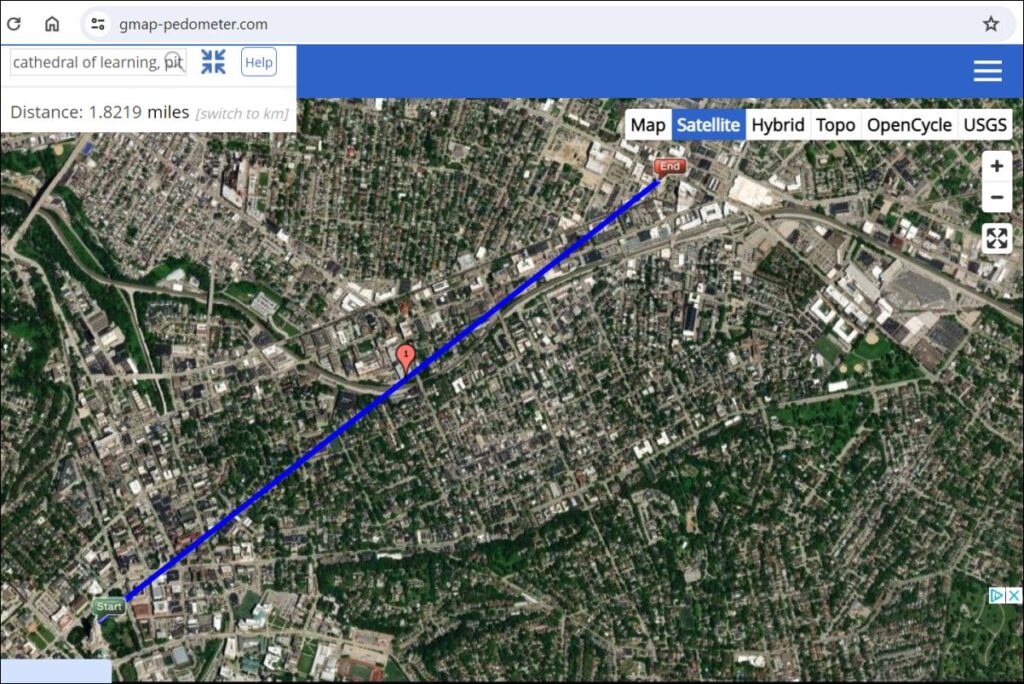

And in case you’re wondering if the Pitt peregrines can see them, the answer is “Yes but not directly.”

The Cathedral of Learning nest faces south-southeast. The East Liberty peregrines face north-northwest. They are 1.82 miles apart but their view from nest to nest is oblique.

Thank you, Adam, for keeping us up to date!

Check out the latest news in the private Pittsburgh Falconuts Facebook group.

(photos by Adam Knoerzer; maps from Google Maps)

13 February 2024

Road Scholar’s Southern Africa Birding Safari was wonderful on so many levels.

Before the trip began, I expected to see many Life Birds. The southern region from the Zambezi River to the Cape has more breeding species than the US and Canada combined. Add to that the winter migrants from Europe and Asia and there were so many birds to see every day. In 13 days of birding I saw or heard 233 species, 207 of which were Life Birds. See the details in my eBird Trip Report here.

My favorite birds were hard to whittle down, chosen for a variety of reasons. Some because I had a pent up desire to see them. Some for their beauty. Some for their behavior. 14 are in the slideshow (thanks to Wikimedia photos) and described below.

No. 1! The secretarybird (Sagittarius serpentarius) is declining and endangered so it was a real treat to see one. These elegant raptors walk slowly scanning the ground for food while their long scaly legs protect them from the venomous snakes they eat for a living. [If the video below spins without playing, click on the YouTube logo at bottom right to watch it on YouTube.]

No. 2: I’ve been wanting to see a Kori bustard ever since I wrote about them in 2009.

No. 3 & 4: Flamingos! We saw greater (Phoenicopterus roseus) and lesser (Phoeniconaias minor) flamingos at Marievale. Greater flamingos have pink beaks, lessers have dark beaks.

No. 5: The black heron (Egretta ardesiaca) looks like a snowy egret in charcoal black. He throws shade to catch his prey.

No. 6: I wanted to see an Amur falcon (Falco amurensis) after I learned about their amazing migration last October.

No. 7: I’ve always liked the French name of the bateleur (Terathopius ecaudatus), an endangered serpent eagle that “tumbles” in aerial acrobatics. In flight bateleurs are easy to identify because their toes stick out beyond their short tails.

No 8: We found a dark chanting goshawk (Melierax metabates) holding a lizard above us that he had caught for lunch. Here’s how he chants.

No. 9: Southern carmine bee eater (Merops nubicoides): Beautiful and acrobatic.

No. 10: Crimson-breasted shrike (Laniarius atrococcineus): Gorgeous in red. (eBird calls it a gonolek. Such confusion!)

No. 11: African paradise flycatcher (Terpsiphone viridis): Colorful and extravagant.

No. 12: The wire-tailed swallows (Hirundo smithii) were an unexpected joy. As we boated up and down the Chobe River the swallows flew around the boat. Sometimes they flew with us, just under the tarp roof, or landed on the edge.

No. 13: Red-billed oxpeckers (Buphagus erythrorhynchus) were easily found on mammals, especially impalas. We saw quite a few perched upside down on a giraffe, plus a pair nesting at Hwange National Park.

No. 14: Male pin-tailed whydahs (Vidua macroura) are boring brown in the non-breeding season but during southern Africa’s summer they are snazzy with long thin tail feathers. At Marievale a male called just outside the bird hide window, then displayed in front of us when a female showed up. Such a show off!

I’ll be telling you more about our trip in the weeks ahead: birds, animals, landscape, people, culture, history, and weather.

Though we did not see a leopard we saw the “leopard of birds.” Stay tuned.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons)

12 February 2024

Winter is back again so we need a good excuse to get outdoors. That excuse has arrived just in time. Join the annual Great Backyard Bird Count this coming weekend, Friday to Monday, 16-19 February.

Count birds at your feeders. Count birds at a park or hotspot. Count alone or with friends. You don’t even have to sign up.

Enter your sightings in eBird or use Merlin Bird ID. All the birds you record next weekend will automatically be included in the Great Backyard Bird Count.

Warm up with an online Merlin Bird ID Trivia Event this coming Thursday, 15 February 8-9pm Eastern time. Learn more and register at the Great Backyard Bird Count page.

Don’t despair that it’s still winter. Your bird feeders will be busy this weekend. It’s time to count birds!

(credits are in the captions)

11 February 2024

Last month I wrote about Victoria Falls or Mosi-oa-Tunya, before I’d ever seen it. Our Road Scholar Birding Tour visited the area twice: the Zimbabwe side on 22 January, the Zambian side eight days later. While there I learned that the falls really are “the smoke that thunders.”

This marked-up aerial view shows the viewpoints where my photos and videos were taken.

The Devil’s Cataract, on the far left side of the falls, is where the crack begins that will some day become the new fall line.

The Danger Point at the far end of the Zimbabwe side is closer to the falling water. It was very misty, almost otherworldly. We wore raincoats.

As we left on 22 January we stopped at the overlook for the old Victoria Falls Bridge that spans the outflow of the Zambezi River. People pay to bungee jump 364 feet from the bridge into the canyon. I did not want to watch.

We went there to find Schalow’s turaco (Tauraco schalowi), a fruit-eating African bird that frequents riparian habitats … and we were in luck! One flew by and landed near us. These eBird photos show its beautiful colors.

On 30 January we returned to Victoria Falls on the Zambia side where the water was even closer and more dramatic. Those who want to walk to Livingstone Island or the Devil’s Pool during low water start their journey on this side, walking 1 km (more than 2/3 mile).

No way! Look how fast the water rushes toward the cliff …

… and falls down the other side.

We crossed the Knife’s Edge Bridge …

… to complete our tour of The Smoke That Thunders.

(credits are in the captions)

10 February 2024

Beautiful sunrises, calm reflections and high water at Duck Hollow were on tap this week in Pittsburgh.

The week began as Winter but ended even warmer than early Spring. The tulips in my neighborhood are well above ground, fortunately without flower buds. One week from today, on 17 Feb, the weather forecast calls for temperatures as low as 19°F.

The tulips survive in my too-many-deer neighborhood because they’re surrounded by buildings and tall fences with no obvious exit other than a narrow driveway.

I thought that the maze of buildings and driveways would protect these Japanese yews in front of Newell-Simon Hall at Carnegie Mellon, but deer found their way in and munched the bushes down to sticks. There’s a lot more to eat here. The deer will be back.

9 February 2024

Like our chickadees, Eurasian blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) are cavity nesters who may nest in backyard boxes.

The nest box shown below was lovingly decorated by the landlord and equipped with a camera to view the comings and goings of prospective renters. This bird seems satisfied and will soon take up residence.

There have been quite a lot of viewings here, but this client was keen to have a better look around inside. Feedback was positive. They felt it was more spacious than they had thought and they were keen on this furnished option. Great views from the front door!#GwylltHollow pic.twitter.com/i90DKbZXFf

— WildlifeKate (@katemacrae) February 7, 2024

(photo from Wikimedia Commons, tweet embedded from WildlifeKate, @katemacrae, located in South Wales)

8 February 2024

In southern Africa, caterpillars of the emperor moth Gonimbrasia belina (or Imbrasia belina) are commonly called mopane worms because they feast on the leaves of mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane). Their final instar is shown above, adult below.

During my trip in southern Africa I did not notice the trees but their oddly shaped leaves caught my attention.

I had no idea of their significance as a place to find food.

Mopane worms are prized as human food. When they reach full size women and children avidly pick them from the mopane leaves, squish out their guts and take them home to boil and sun dry. When fully prepared the mopane worms look like this:

I had the opportunity to sample mopane worms at Dusty Road Township Experience, an award-winning restaurant in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe where we ate traditional food.

What did mopane worms taste like to my naive palate? Earthy. Crispy. Very earthy.

Perhaps the flavor was so earthy because I ate the head first. In Zimbabwe this makes no difference but in Botswana they take the heads off before they eat them because the heads change the taste. I wish I’d known so I could have tried it both ways.

Learn more about mopane worms and how to cook them in this video by Emmy @emmymade. She tastes them both ways and describes their flavor at 3.5 minutes into the video.

(credits are in the captions)