20 February 2024

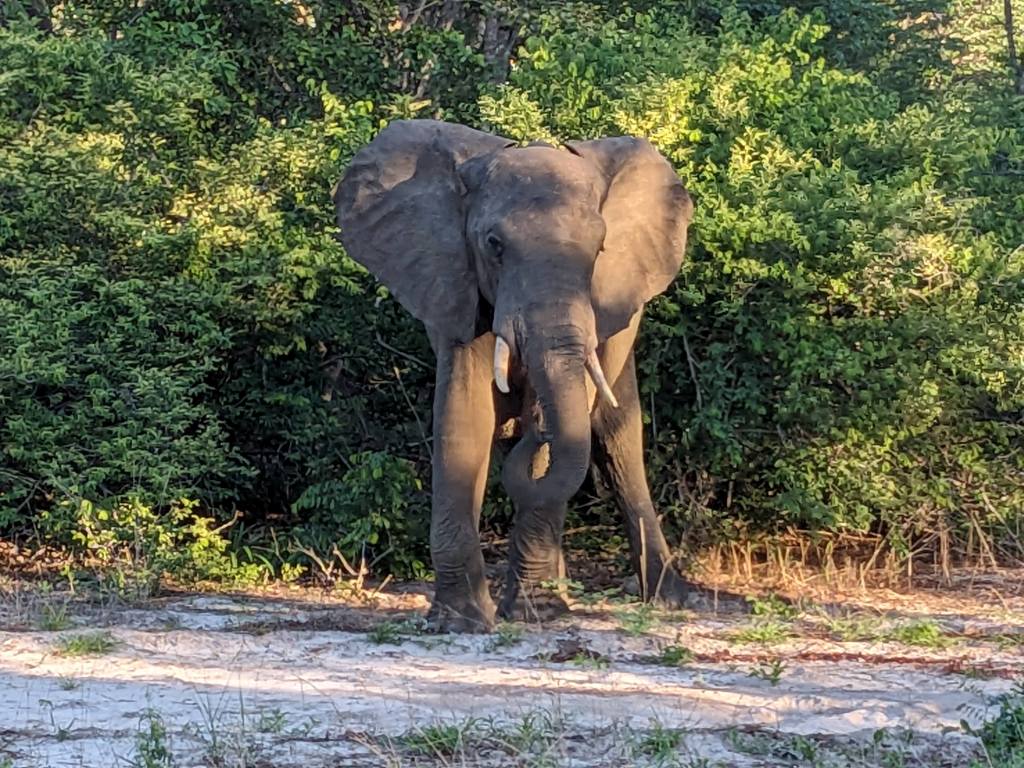

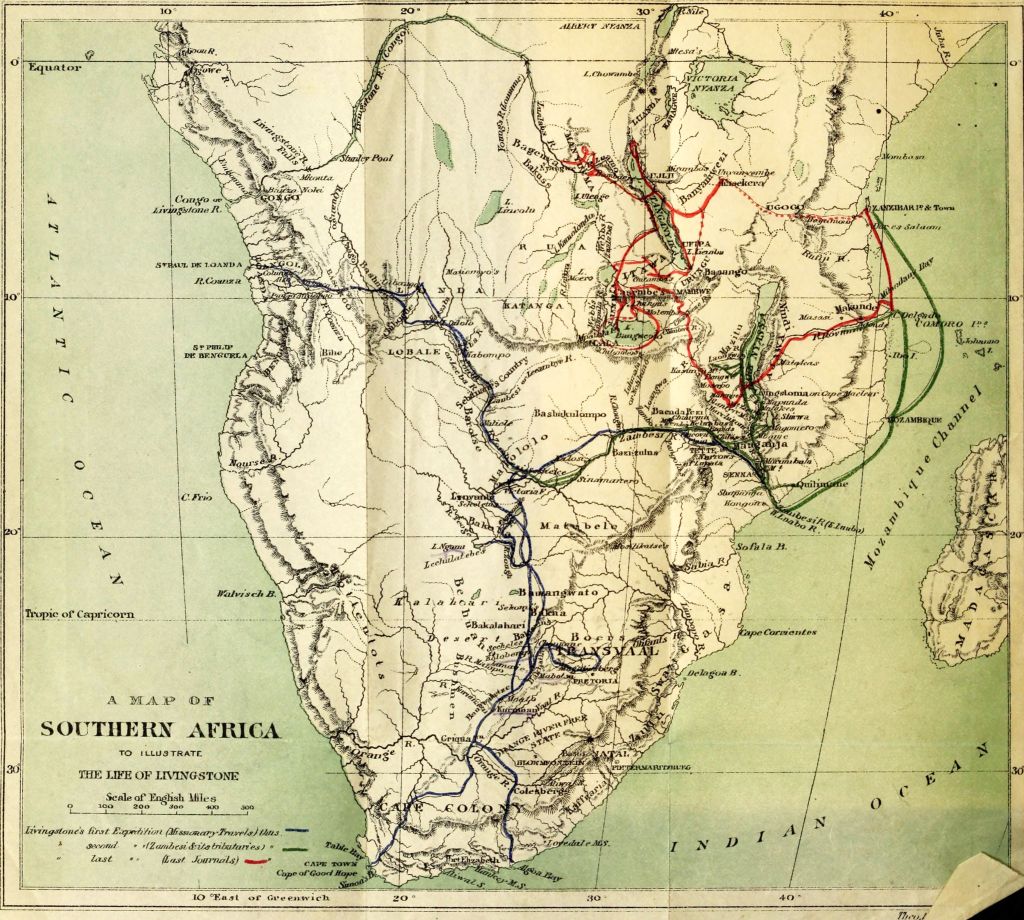

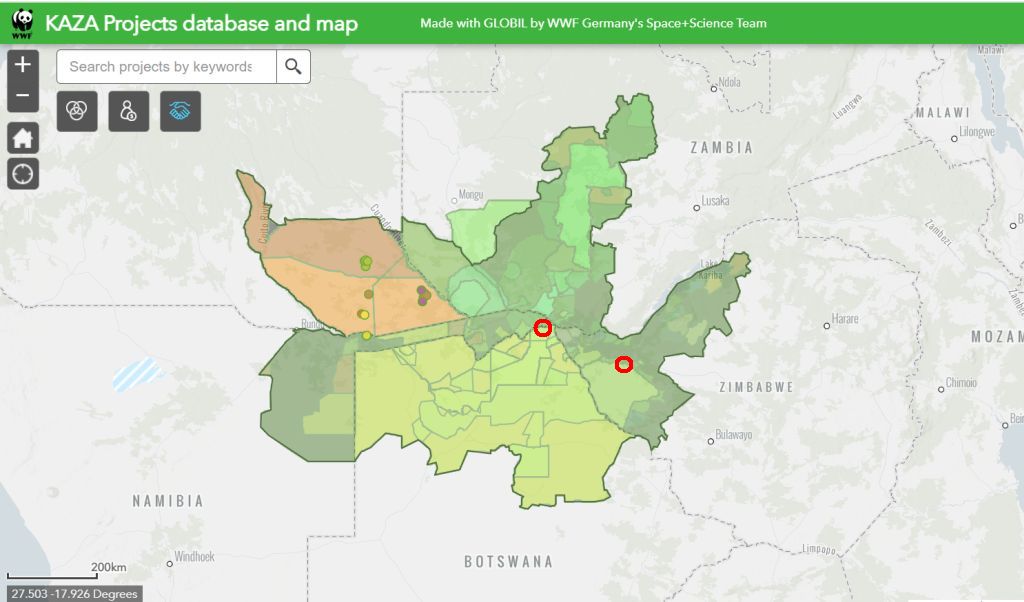

When I signed up for Road Scholar’s Southern Africa Birding Safari (19 Jan-2 Feb 2024) I knew I would see hundreds of Life Birds but did not realize there would be an added bonus. Our tour was in the KAZA region, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, where wildlife roams freely. KAZA is home to the largest population of African elephants in the world.

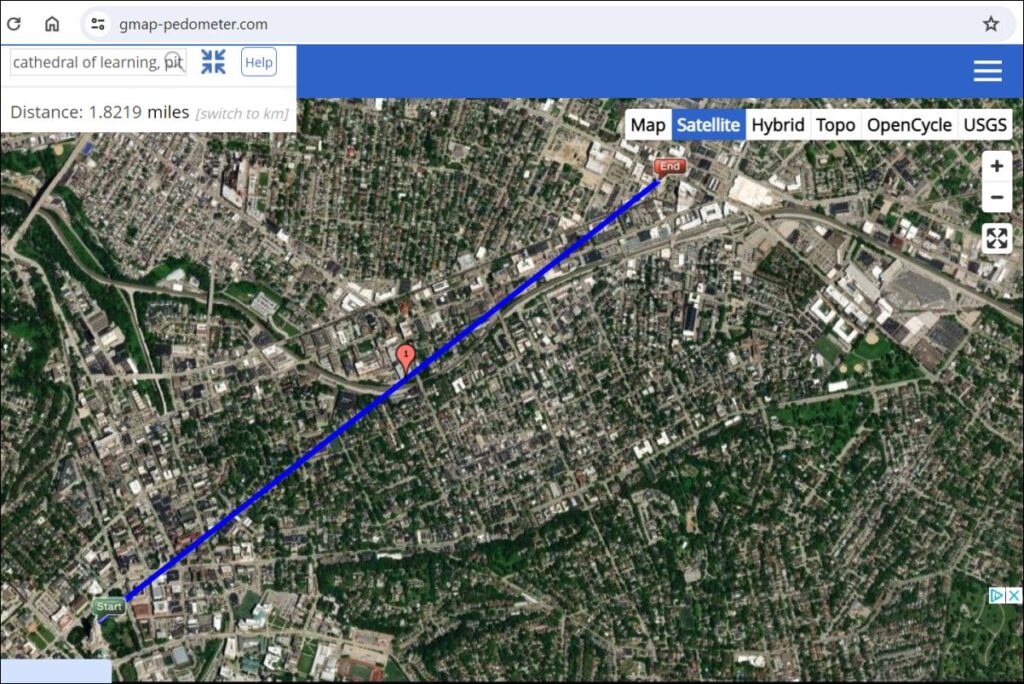

We saw elephants every day in the areas marked on the KAZA map above. Here is what I learned.

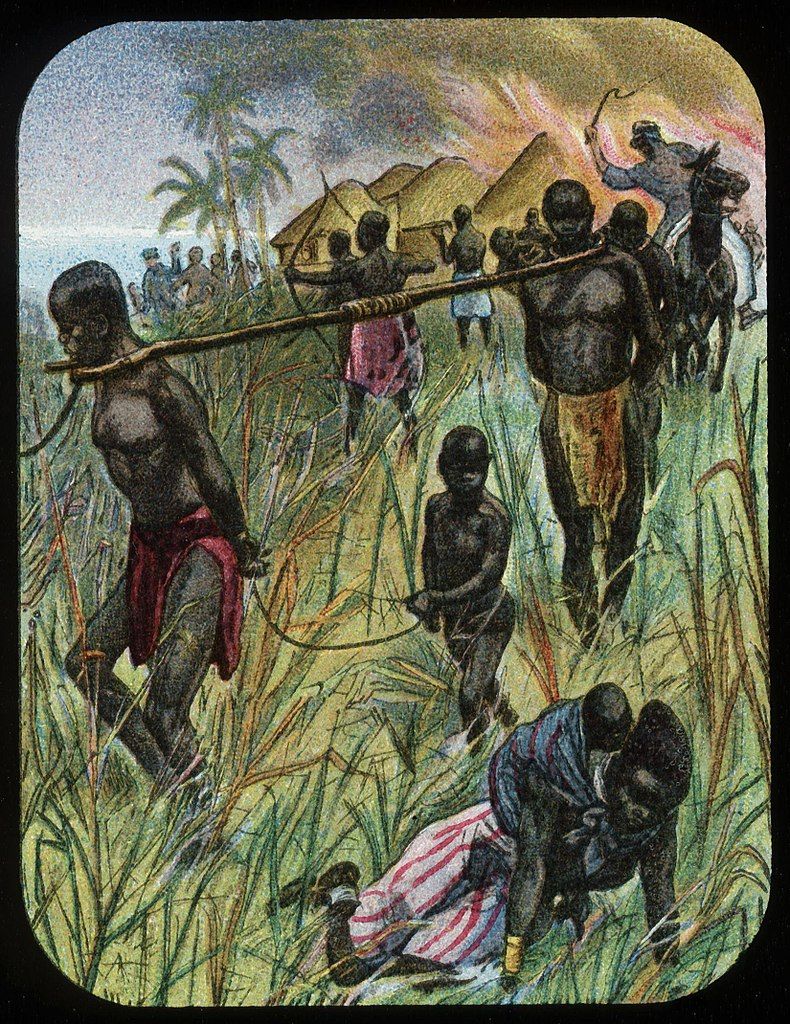

African bush elephants, also called African savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) are an endangered species having gone from a high of more than 2 million in 1800 to a low of 1,000 in the early 1900s. Now they number about 45,000 but are threatened by human encroachment, poaching, big game hunting (which prizes large tusks thus removing the best genes) and climate change.

Elephants live near fresh water because they must drink and bath so much. Climate change brings drought. Drought kills elephants. This summer there is a drought in southern Africa because of El Niño.

African elephants eat trees, leaves and even the cambium layer of bark. To chew this material they have four molars which they replace throughout their lives until they lose their last molar at age 40-60. Without molars they starve, a common cause of death. (This also happens to white-tailed deer who starve when their teeth wear out.) Tusks are modified teeth and both males and females have them.

We learned about elephant behavior by observing them.

Elephants lived close to us at Khulu Bush Camp. At night they roamed between our tent buildings; I could hear them munching. At midday they came out of the forest to the watering holes near camp to drink and coat themselves with mud against the 97°F afternoon heat.

The camp provides a pool of water and minerals attractive to elephants near the dining area which is elevated and protected by a small boma. We could safely view the elephants as they came quite close.

The females and young elephants move to the watering hole in a matriarchal herd.

At first only one elephant drank from the pool.

Then the crowd came close.

Two days later a bachelor group showed up while an older male was drinking at the pool. The older male challenged them with a stern look. The younger males backed off.

Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe:

On safari at Hwange National Park we saw a male elephant hanging out with a lone female. She disappeared into the forest while he appeared to be annoyed that we showed up. Perhaps he was guarding her as his own.

Chobe National Park, Botswana:

From a pontoon boat on the Chobe River we saw wildlife walking the shore at Chobe National Park. In late afternoon a small herd of elephants came to the river to drink and douse themselves with water. As this mother left the river we saw her baby nursing.

All these photos were taken with my cellphone! What a privilege to see African elephants so close.

p.s. Despite the threats to elephants there is one activity that helps them. Wildlife tourism is the #3 industry in the region & it prompts governments and people to protect wildlife.