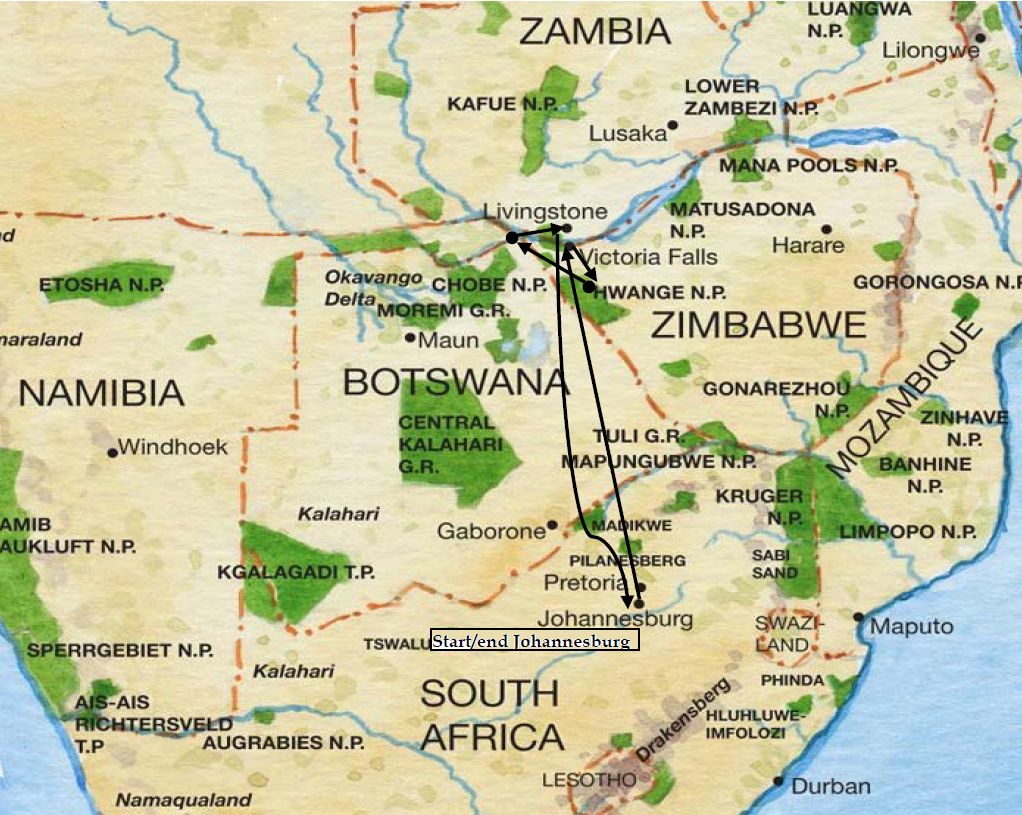

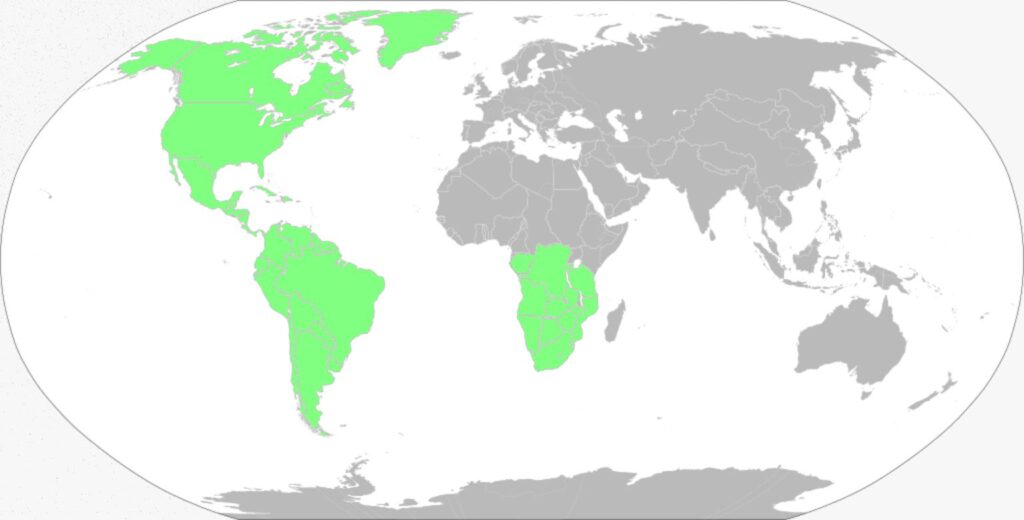

25 January 2024: Day 7, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe — Road Scholar Southern Africa Birding Safari. Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

The Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori) is a large ground bird native to Africa that forages by walking along, repeatedly poking it’s beak to the ground. The male of this species can weigh more than 44 pounds and is reputed to be the heaviest bird that’s able to fly.

The males use courtship displays to attract and breed with as many females as possible, then take no part in raising the young. Dancing and neck puffing are some of the many tricks they use to attract the ladies.

I’ve wanted to see this bird since 2009 when I found out they tip the scales for flying birds. My best chance may be at Chobe National Park, Botswana in three days time (28 January).

Fingers crossed that I’ll see him while I’m here. He doesn’t even have to fly for me to be enthralled!

Find out why he’s at the top limit of flying birds in this vintage 2009 article.

p.s. I *did* see a Kori bustard. In fact, I saw a pair of them walking near Hwange National Park Airport on 26 January.