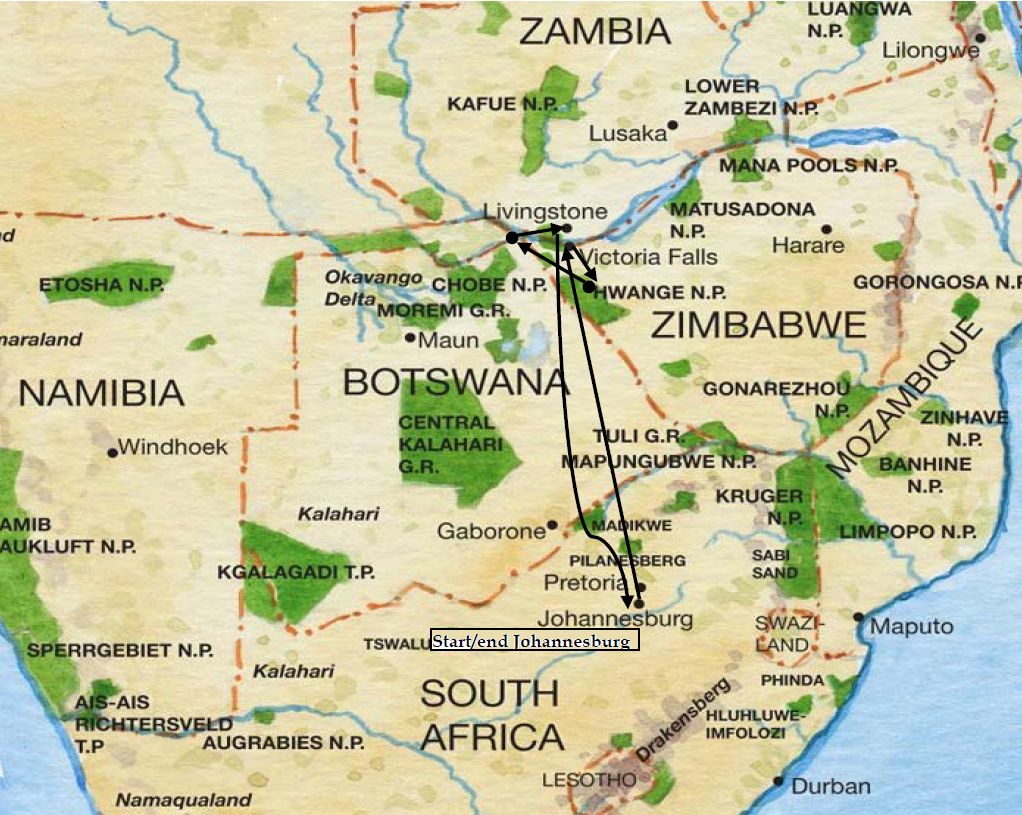

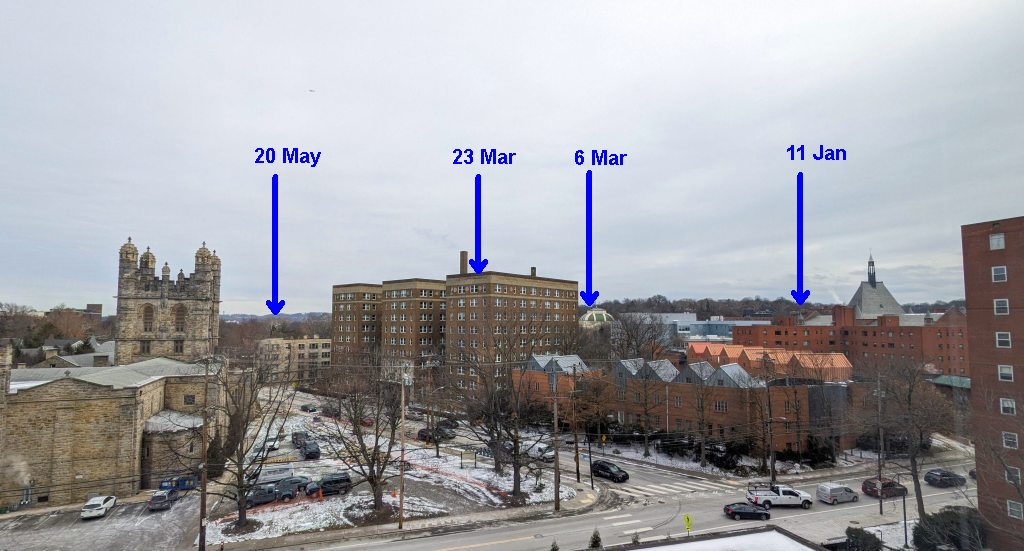

21 January 2024: Day 3, Marievale Bird Sanctuary — Road Scholar Southern Africa Birding Safari. Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

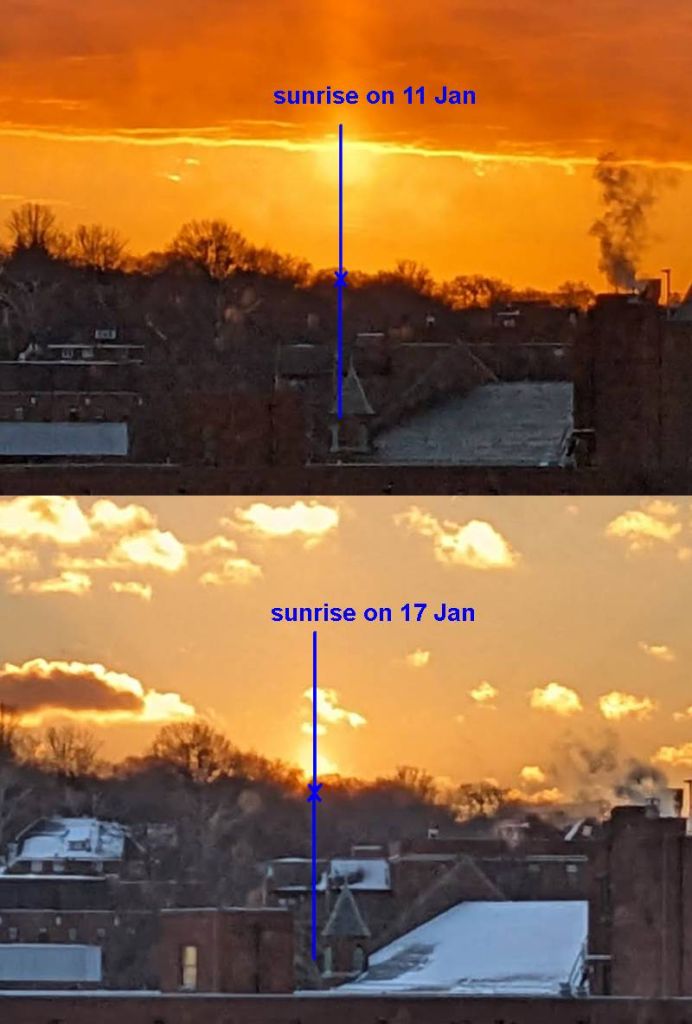

Today we’re birding at Marievale Bird Sanctuary southeast of Johannesburg. In the third week of January it’s mid-summer in South Africa, similar to July in the U.S.

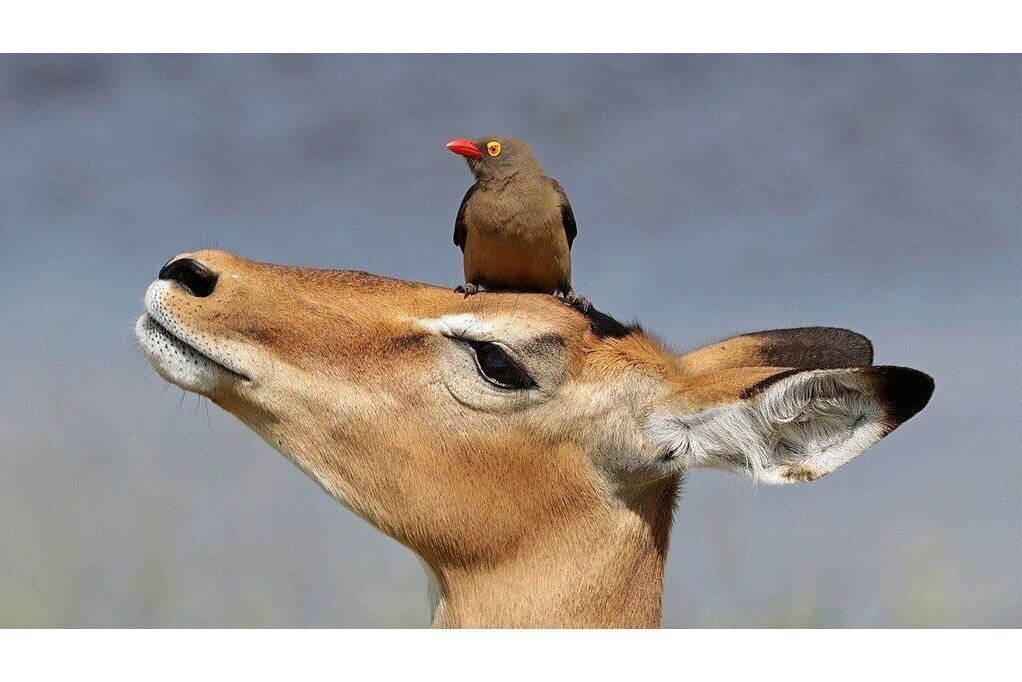

Many of the birds at Marievale are similar to those in Florida. For instance, the African spoonbill pictured above resembles our roseate spoonbill. (I prefer the roseate spoonbill because it is beautiful pink.)

There are also several species that are native in both places: fulvous whistling duck, common moorhen, cattle egret, great egret, glossy ibis, barn swallow and peregrine falcon. At Marievale not every bird is a Life Bird for me.

See Marievale’s birds in the 8-minute video below and you, too, may conclude that South African marsh birds are the same as Florida’s and yet they are different. After the video I’ve provided a table with the names of similar North American species.

List of Birds in the Marievale video above and their familiars in North America.

(credits are in the captions)