16 November 2023

Crow news this week! from Phillip Rogers:

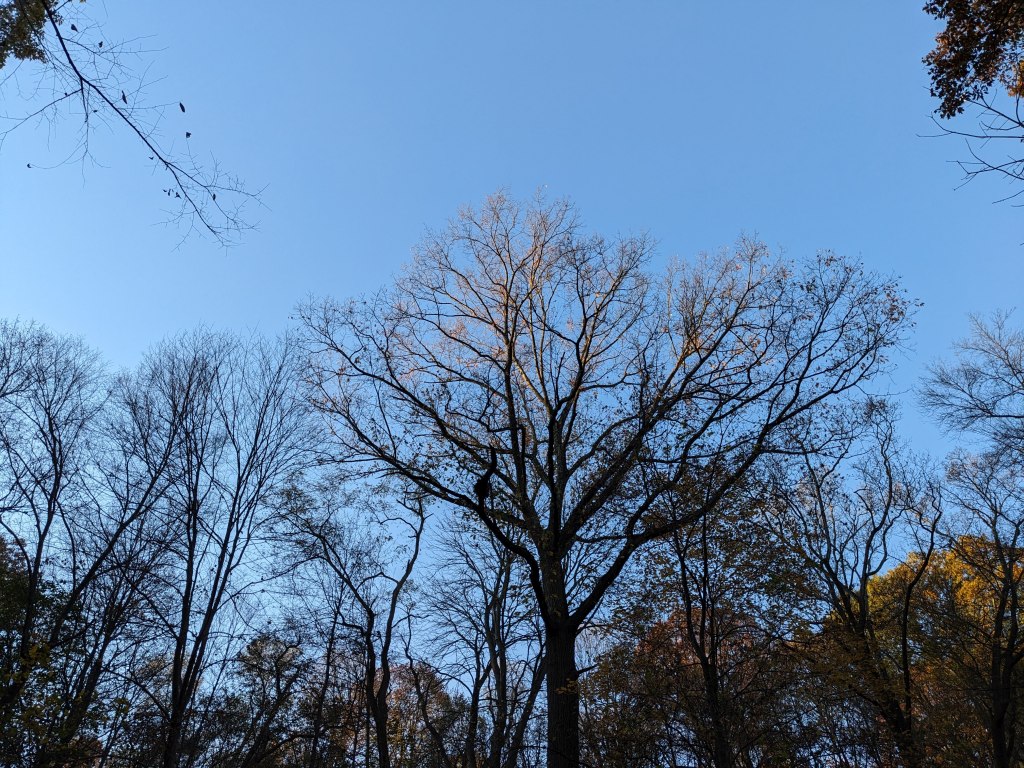

Hi all! There are hundreds (probably thousands?) of crows that roost every night outside the Cathedral of Learning at Pitt. Coming in at sunrise it feels like a scene straight out of Hitchcock’s The Birds movie. This evening I saw a man (facilities or groundskeeping employee?) using loud clapping and flashing lights to try to get the birds to leave (short video below). The sidewalks all around are littered with droppings, which is presumably why they want the birds gone.

— Phillip Rogers comment to PittsBirder Chat

I remembered a similar episode 10 years ago when Pitt used bird distress sounds to scare the crows. Back then it worked …

… but crows are really smart. They soon figured out the recordings are fake and promptly ignored them.

By 2020 Pitt had to change tactics. Crows don’t like sudden loud noises and flashing lights when they’re trying to sleep so they made hinged wooden clappers to scare the crows.

The clappers worked for a while … but crows are persistent so this week Pitt had to add flashing lights.

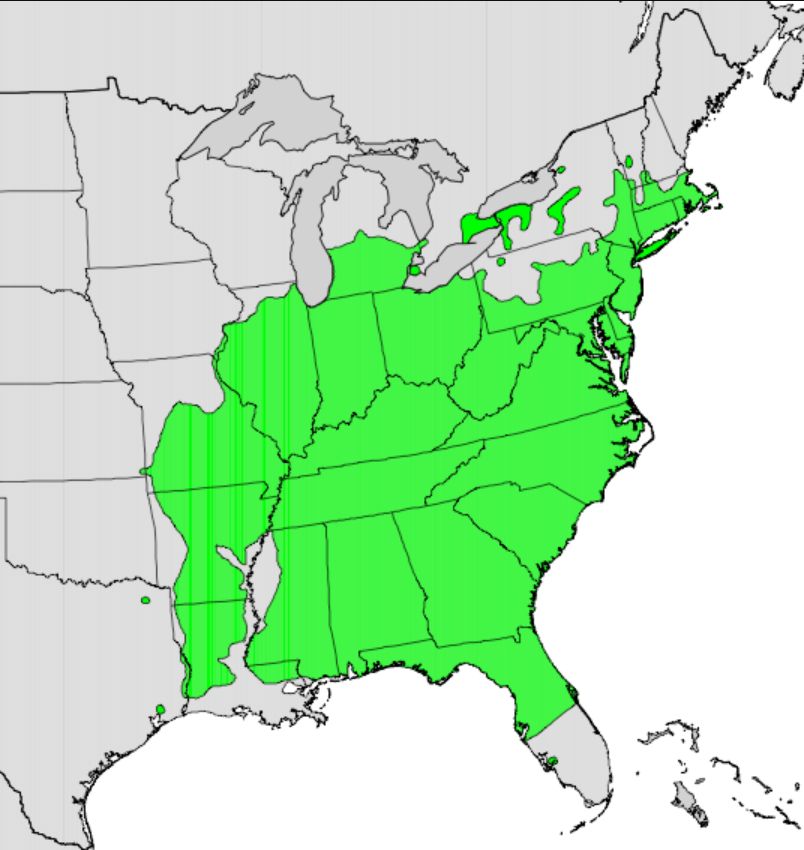

This tug of war with winter crows happens every year when thousands come to Pittsburgh to spend the winter. By mid-November the crows wear out their welcome in Oakland and are “encouraged” to move to other locations.

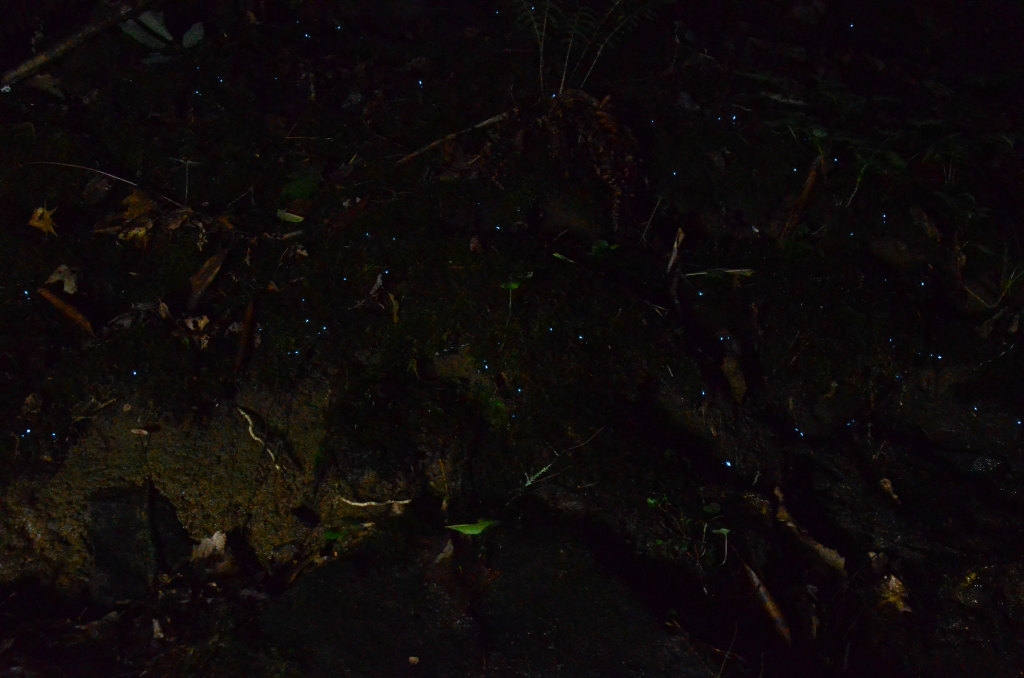

Right now there are 6,000 to 10,000 crows trying to sleep at Pitt and until they stop roosting there, I live in their flyway. This video from early Nov 2020 shows what it was like outside my apartment on 5 November.

By the end of the year the crow flock will number 20,000 and the roost will have moved at least once or twice. Where will they be on 30 December when I have to count crows for the Pittsburgh Christmas Bird Count? I’ll need to find out.

(credits are in the captions)