1 November 2024

In 1944 the US Army Corp of Engineers completed a flood control dam across the Youghiogheny River that created a lake into Maryland. The project included a new bridge for US Route 40 because the Great Crossings Bridge at Somerfield would be submerged and so would the town’s low lying streets and buildings.

Normally the lake is full and beautiful. You would never know there was a bridge underneath it.

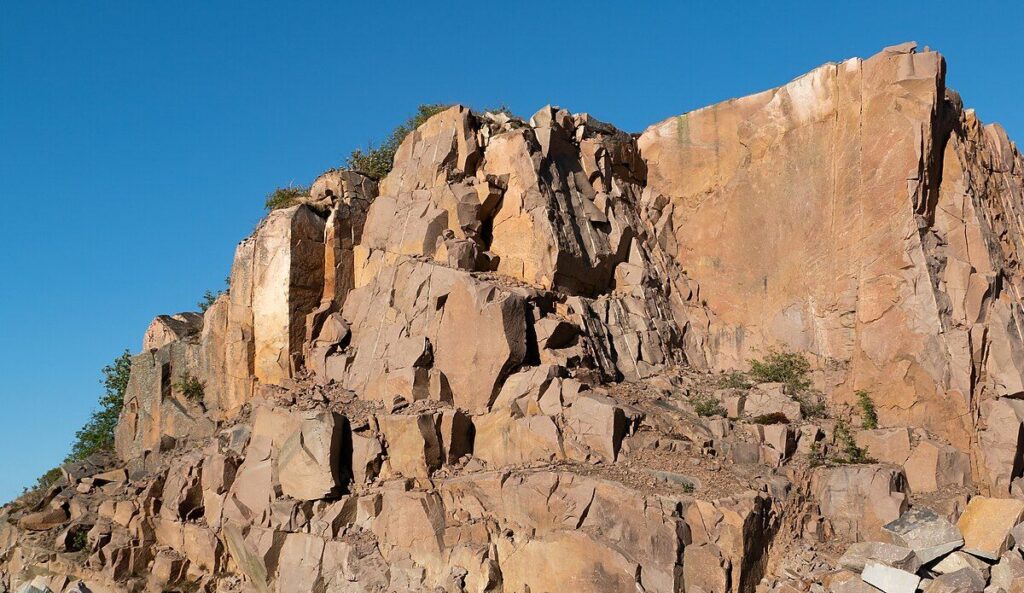

But this year a drought in the Youghiogheny watershed has lowered the lake so far that you can walk out on the old Great Crossings Bridge.

This Google Map shows both bridges.

embedded Google Map showing submerged Great Crossings Bridge north of US Route 40

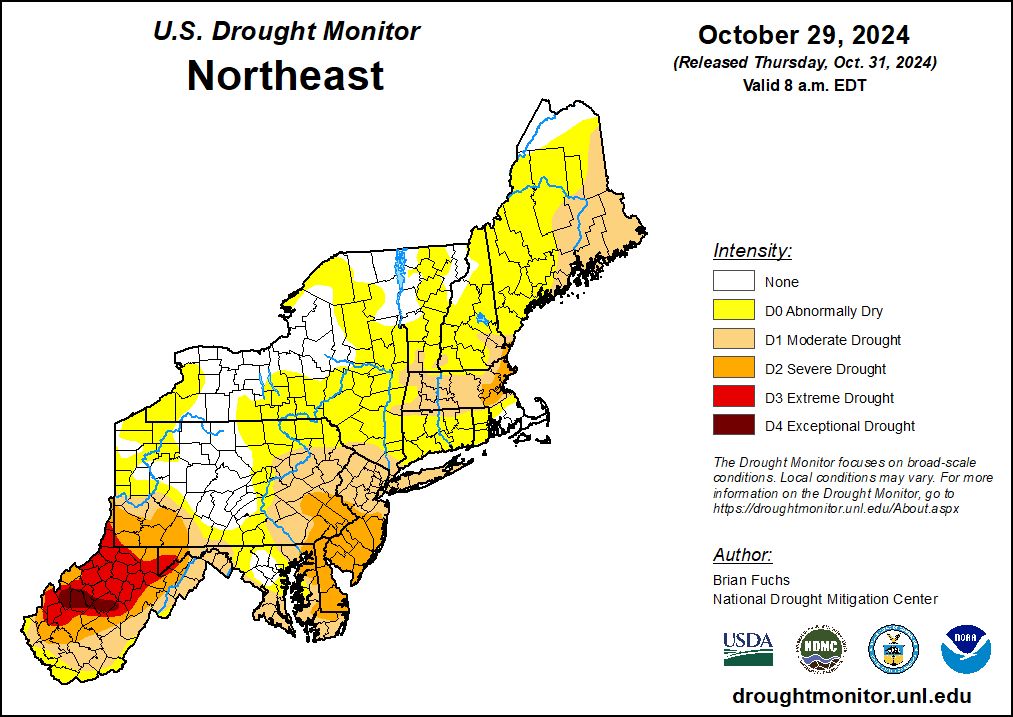

Pittsburgh is not in severe drought so it’s hard to understand how this lake could drop unless you know where the river comes from. The Youghiogheny is a north-flowing river with headwaters in the mountains of West Virginia and Maryland. Notice that the rest of the Monongahela river basin starts in West Virginia as well.

The headwaters of both the Youghiogheny and Monongahela have been in drought since early July. At this point the drought is Extreme to Exceptional in western Maryland and West Virginia.

Water levels have dropped in both rivers but the Monongahela cannot afford to get too low because it carries a lot of barge and boat traffic.

However, there is water upstream to feed the Monongahela. Releases from Youghiogheny River Lake have, in part, kept the Mon navigable.

And so the old bridge emerges from the deep.

p.s. This isn’t the first time the old bridge has been exposed.