18 April 2023

Black-tailed godwits (Limosa limosa) are large shorebirds with a worldwide distribution but are listed as Near Threatened because their population declined 25% in only 15 years, 1990-2005. Two thirds of them breed in Europe. In fact almost half the worldwide population breeds in the Netherlands alone.

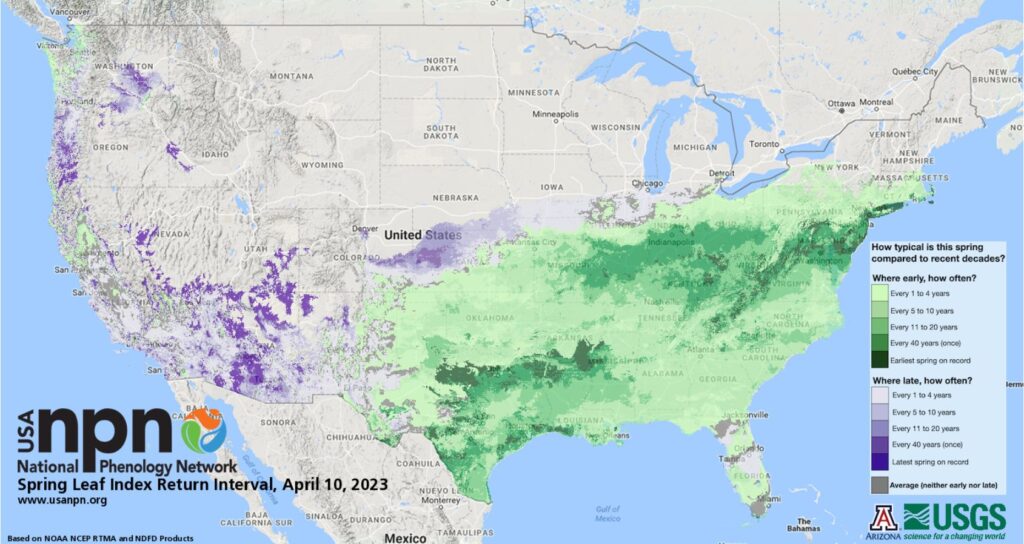

The European breeders spend the winter in the Mediterranean and Africa including at the Tagus Estuary at Lisbon, Portugal. During spring migration the Tagus hosts up to 40% of all the black-tailed godwits on Earth. Anything that permanently disturbs the Tagus could hurt the godwits.

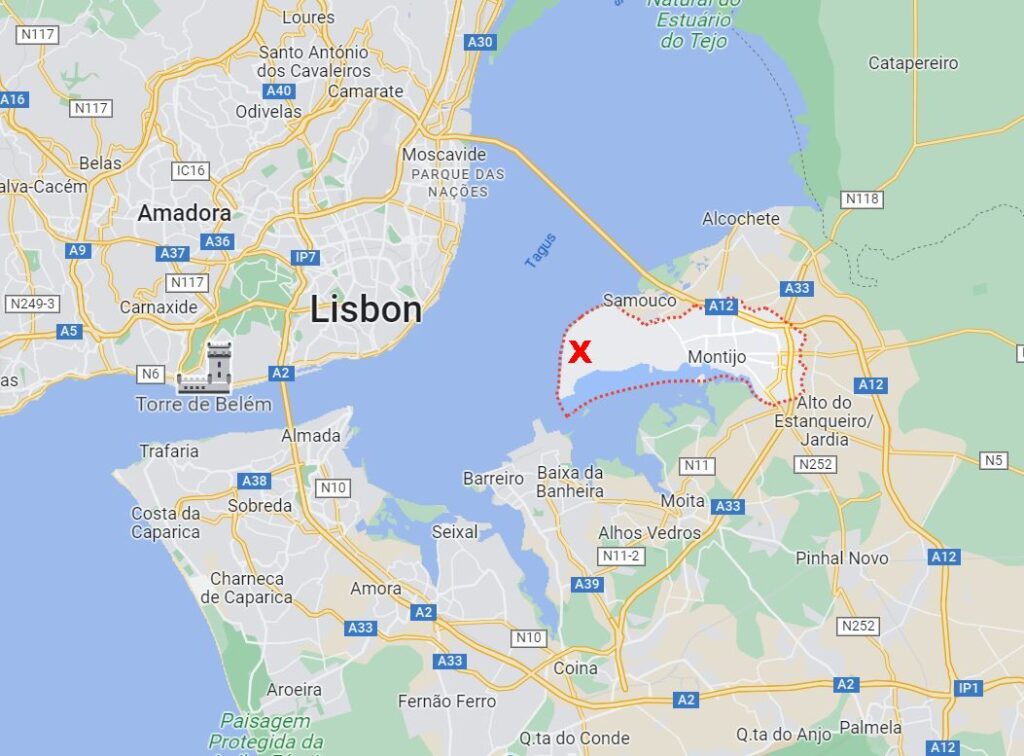

Two decades ago Lisbon, Portugal decided they really need a new airport so they proposed siting it at a former air force base across the Tagus in Montijo.

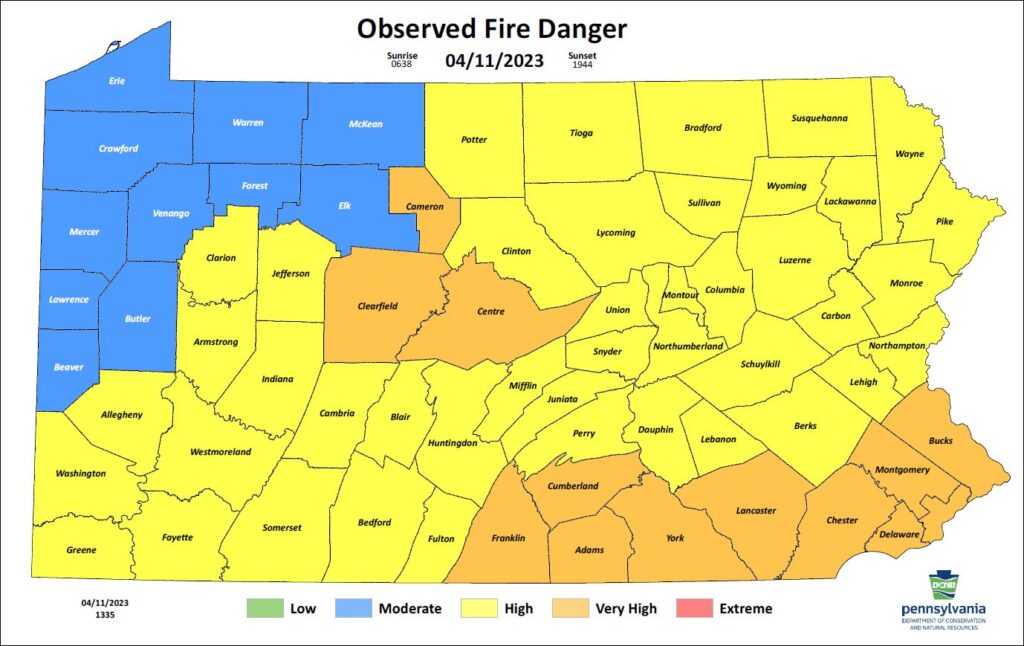

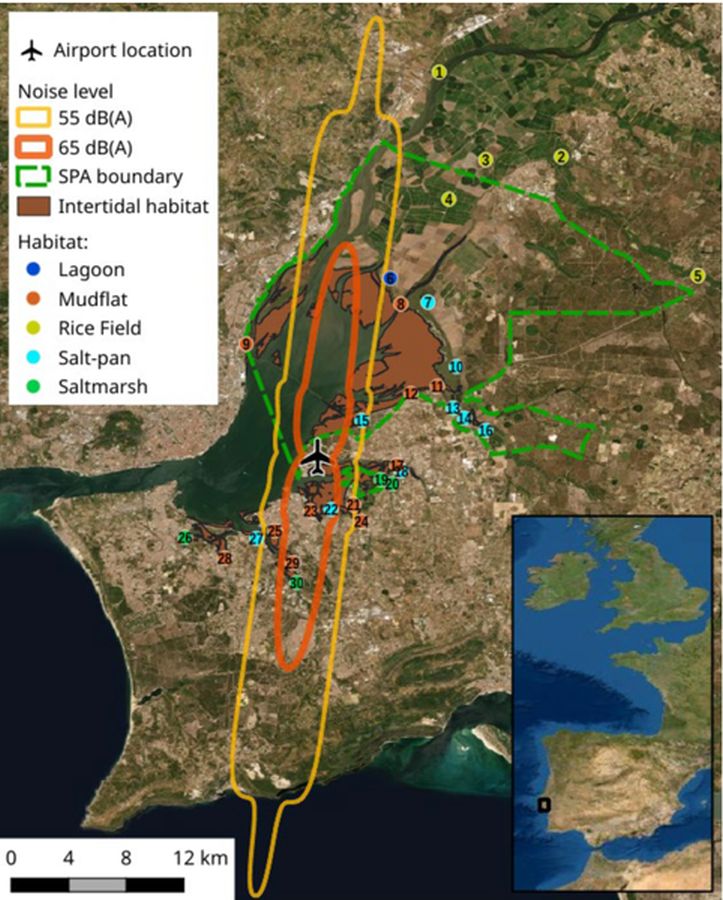

The Montijo Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) counted black-tailed godwits at feeding and resting sites and calculated how many godwits would be disturbed by the noise of air traffic at 65dB (decibels) (orange outline below, 55dB is the yellow outline). The airport’s EIA said only 0.46–5.5% of the godwits would be disturbed.

Though the EIA used the counting techniques that we use in eBird — the number of birds at rest or in the air at specific points — it doesn’t tell the whole story.

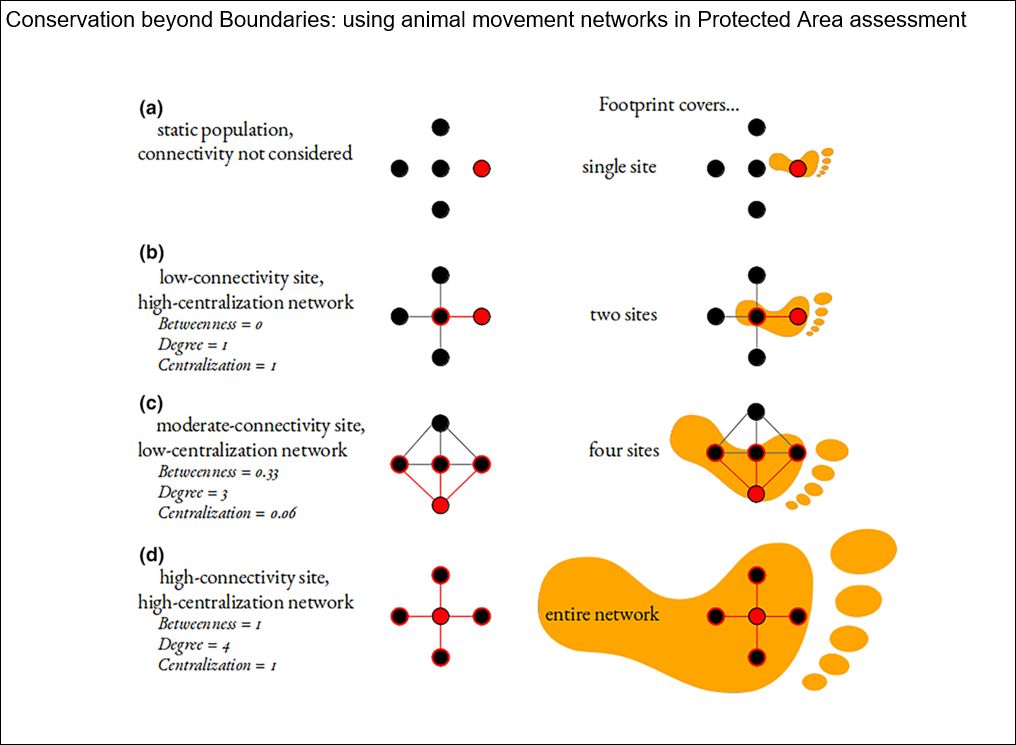

Josh Nightingale, a PhD student with the University of East Anglia and Portugal’s University of Aveiro, decided to study the birds’ flight paths and calculate their larger usage footprint in the Tagus Estuary. The more connections they make, the bigger the footprint.

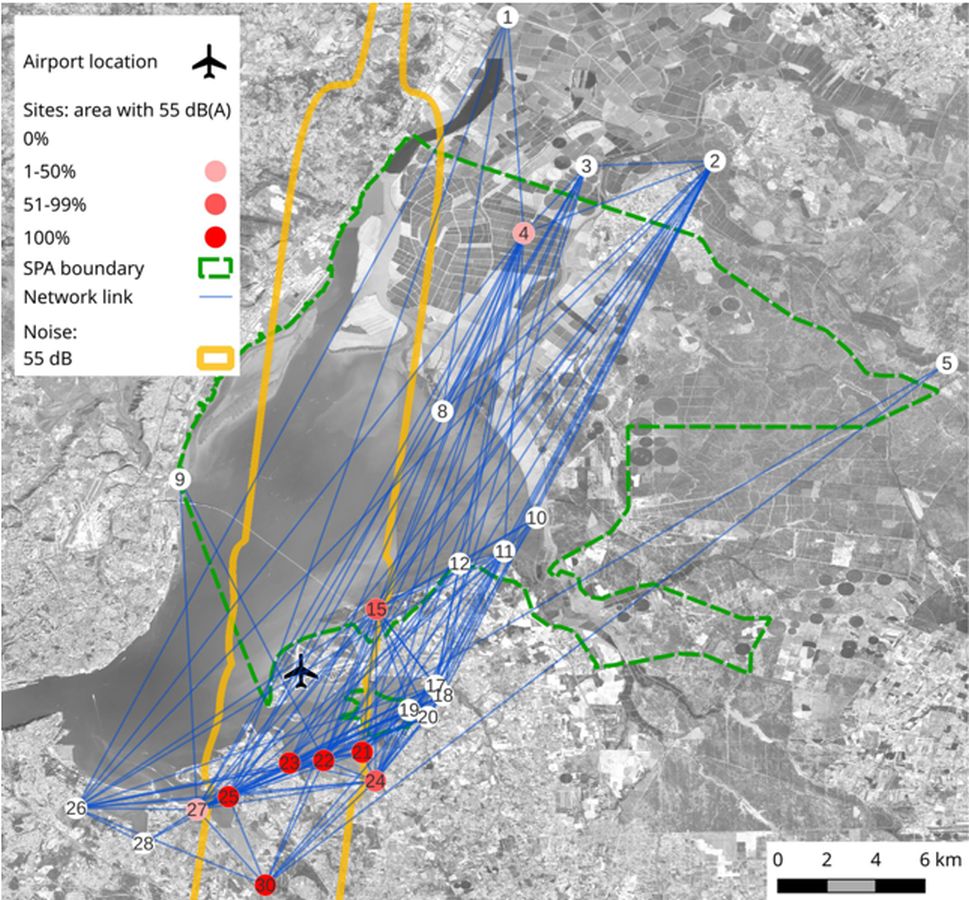

Fortunately many black-tailed godwits are banded so Nightingale could use 20 years of location data on 693 banded godwits, many seen twice on the same day in the Tagus area. He then drew connections from site to site to create the godwits’ airspace network. Nightingale also used a 55dB noise plot because that level of noise disrupts 50% of the birds.

Nightingale concludes:

Frequent disturbance by aircraft is known to have fitness costs for waders by increasing their energy expenditure, and may cause permanent avoidance of habitat if chronic with long-term consequences for site occupancy. The Tagus godwits’ frequent trans-boundary movements mean that 44.6% of the SPA’s godwit population would be exposed to noise disturbance from the proposed airport, and 68.3% of individuals overall. This compares with estimates of 0.46–5.5% in the airport’s EIA.

— “Conservation beyond Boundaries: using animal movement networks in Protected Area assessment” by J. Nightingale et al at ZSL Publications

Nightingale’s paper was published this month in ZSL Publications. Fortunately the Montijo site was placed on the back burner last July. Fingers crossed that this paper tips the balance in the godwits’ favor.

In cases like these, if you want to save birds you have to count differently.

p.s. Read more about this study in Anthropocene Magazine: How You Count Birds Affects Airport Design and Permitting. Or this summary in Science Direct.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and by Keith Gallie via Creative Commons license on Flickr; Lisbon-Montijo map screenshot from Google maps, additional map and diagrams from“Conservation beyond Boundaries: using animal movement networks in Protected Area assessment” by J. Nightingale et al at ZSL Publications. Click on the captions to see the originals)