7 June 2023

At 6:30pm on Monday 6 June, Mark Catalano of Wildlife In Need Emergency Response was working dispatch in Central PA, making phone calls and sending texts and emails on behalf of a juvenile peregrine in a tiny dog park in Downtown Pittsburgh. The juvie needed assistance to be placed up high to start over on his first flight. Meanwhile Leslie McIlroy was in the dog park, protecting the bird from the visiting dogs.

Mark called the PA Game Commission but he knew it would be a long wait for a Game Warden. Since Mark is from Northumberland, PA he didn’t know any local peregrine contacts so he asked his wife to search the Internet for “Pittsburgh peregrine.” She found me, Mark sent me photos, and I told him about the Rescue Porch.

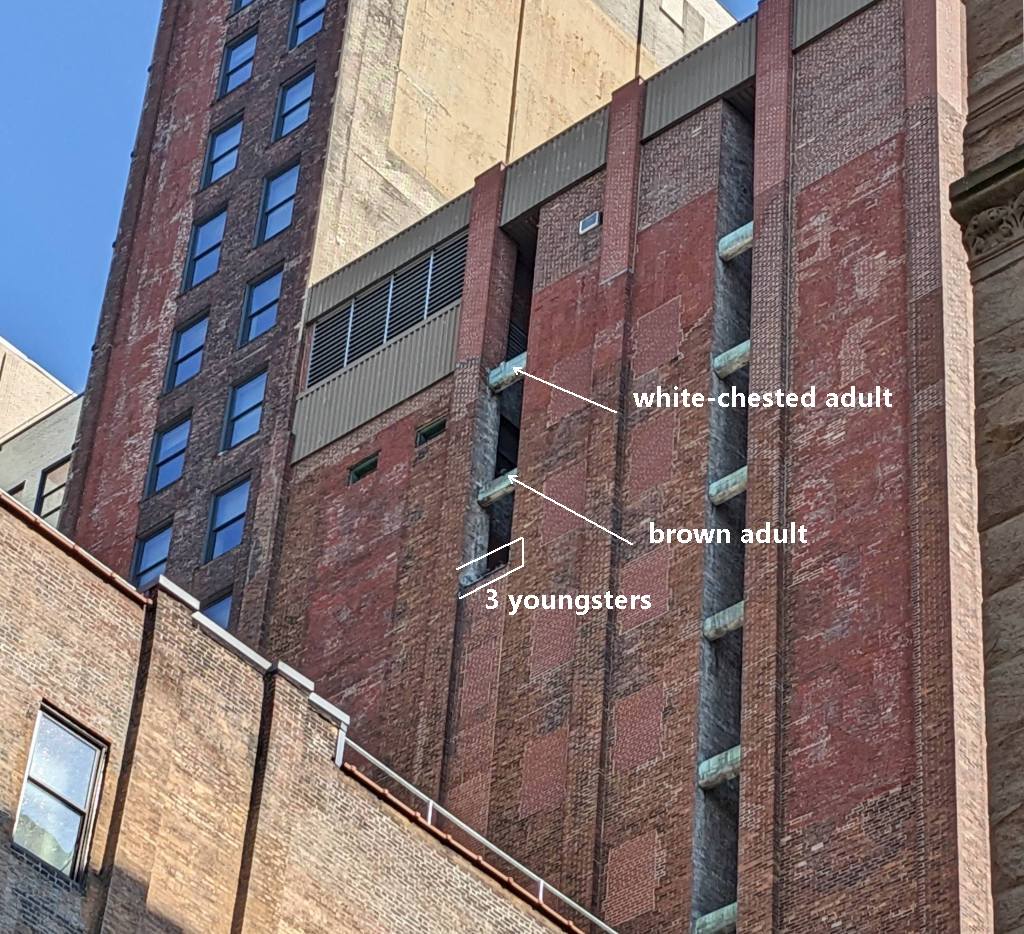

The Rescue Porch is a high balcony across the street at Point Park University’s Lawrence Hall. Another juvie had already tried it out this week, as seen by Diane Walkowski and Lori Maggio at 1:30pm on Sunday 4 June. (White arrow points to the bird.)

Every year one or more fledglings ends up on the Rescue Porch. The Third Avenue ledge is so low and tucked away that fledglings land on the ground on their first flight when they don’t yet have the upper body strength to fly up and away.

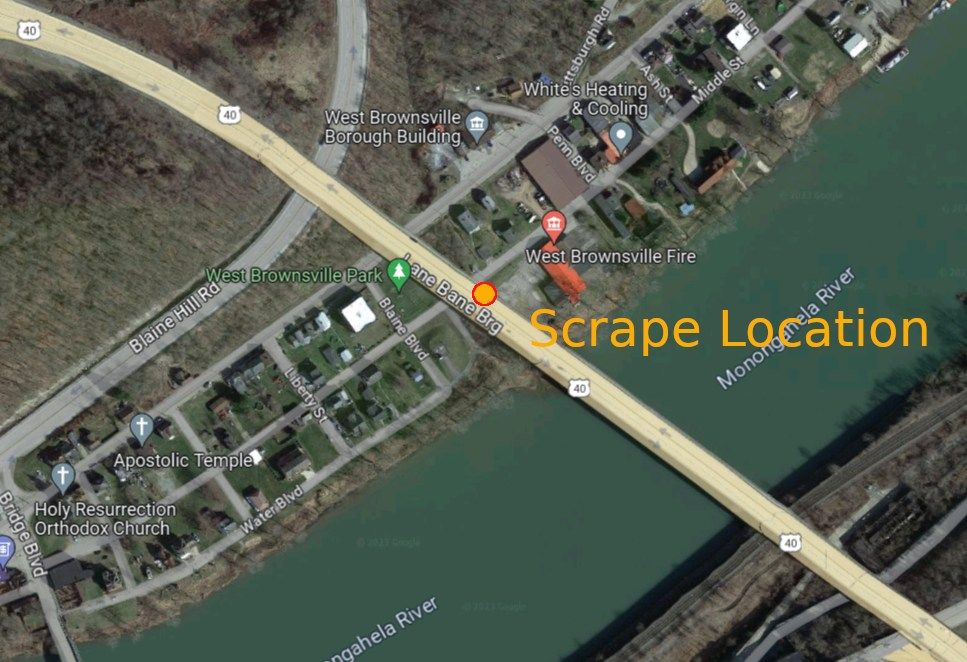

Monday’s bird was stuck in a place I’d never heard of. It turns out that this narrow space under construction in 2021 became a tiny dog park with a tiny patch of grass. The yellow arrow points to a 2021 juvie who eventually landed in here. This year’s juvie hopped up to the low windowsill on the righthand wall, only two feet off the ground (photo at top).

Many thanks to Mark Catalano for starting the rescue and to Leslie McIlroy for guarding the bird until the Game Warden arrived three hours later.

Meanwhile, no news is good news. Sunday’s bird is out and about. Monday’s bird probably flew on Tuesday. Will the third youngster need a rescue too? Time will tell.

Click here for photos of the nest site and all three youngsters about to fly on 3 June.

(photos by Leslie Mcilroy via Mark Catalano of Wildlife In Need Emergency Response, Lori Maggio and Kate St John)