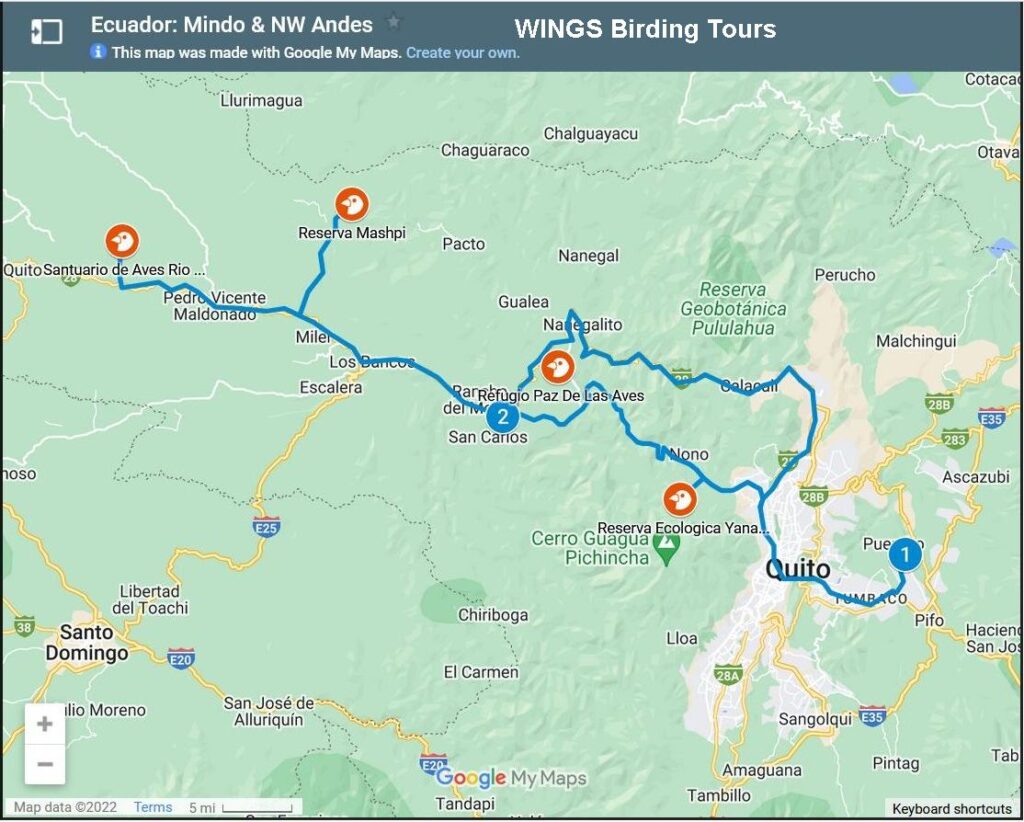

31 Jan 2023, WINGS in Ecuador: Day 3, birding in Mindo and the NW Andes

Now that we’re based at Séptimo Paraíso Lodge in the Mindo Valley we expect to see this iconic bird several times in the next five days.

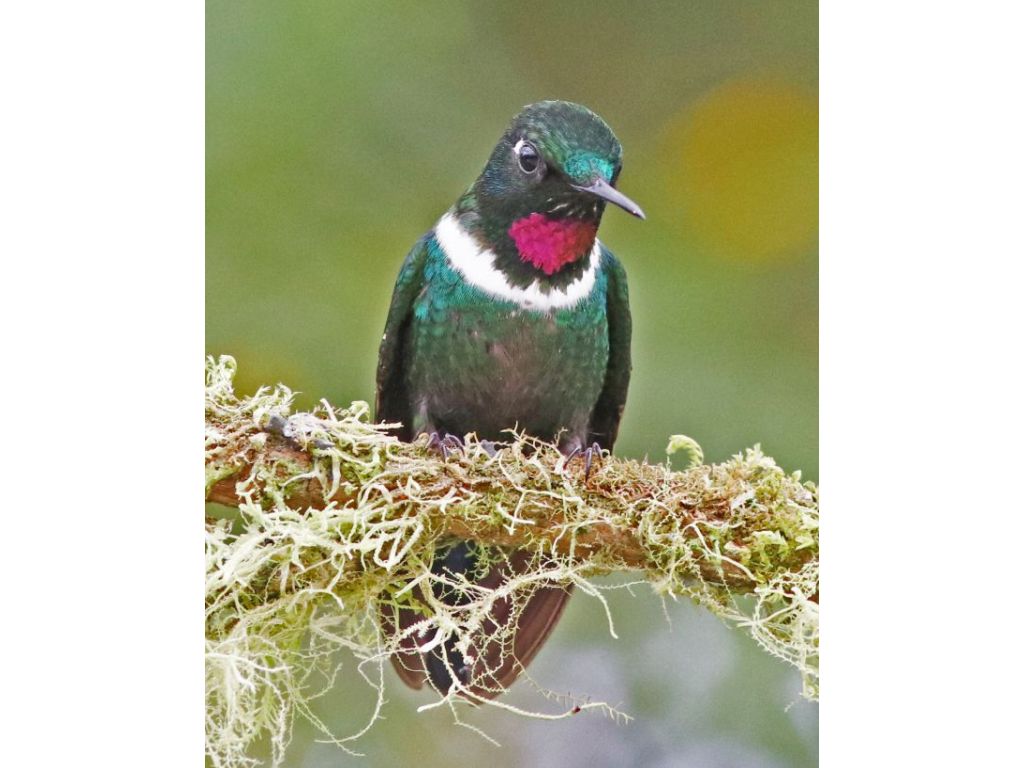

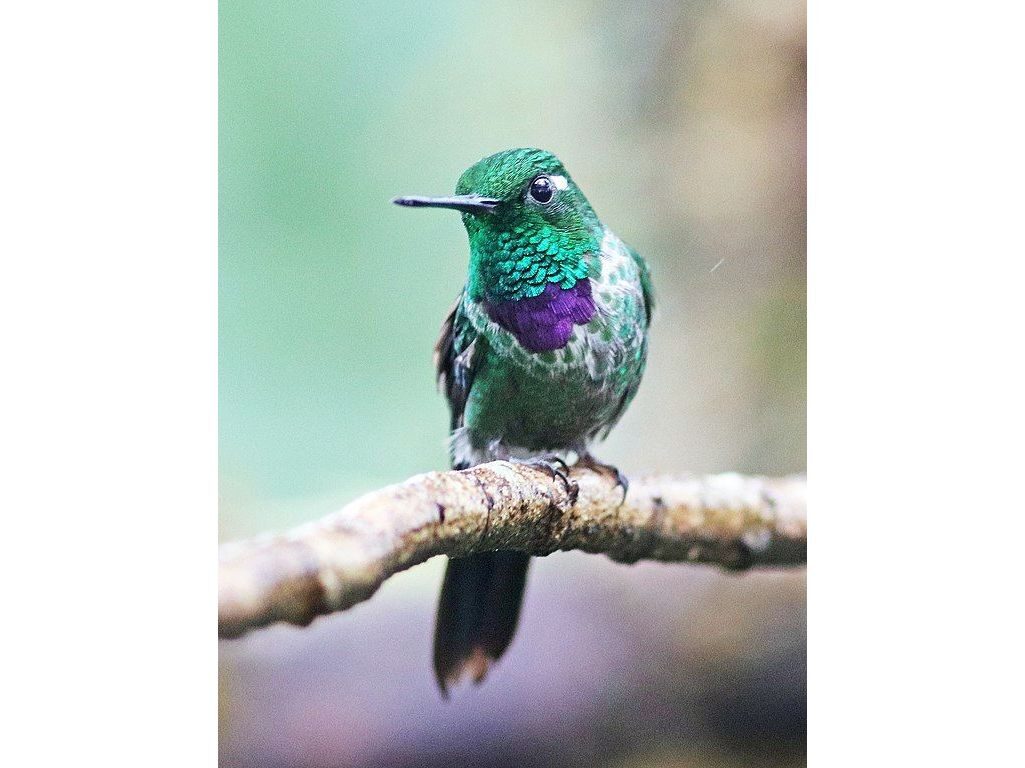

Bright and colorful, the toucan barbet (Semnornis ramphastinus) is about the size of a starling though heftier. He uses his short fat beak to eat fruit, squeeze nectar from flowers, and dig nest holes in trees.

Toucan barbets are very social, living year round in a family group of six+ birds that claim 30 – 40 acres of mountain forest. The group consists of the breeding pair plus their offspring from prior years who help raise the young during the February-to-May (or as late as October) breeding season.

The group starts the day with a duet to tell the neighbors: “Good morning! We are here! This territory belongs to us! We will fight you if you come here!” Other groups will sneak onto their land if they think the owners are far away.

Watch them eat, preen and “sing” in this video.

video from Edison Ocaña on YouTube

p.s. Seen at Reserva Amagusa on 4 Feb 2023.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, video from Edison Ocaña on YouTube, online resources: Birds of the World: Toucan barbet)