11 January 2023

Cement cracks. Rocks erode. Why does ancient Roman concrete last for thousands of years while ours falls apart in only 50?

The 2,000 year old concrete at the Roman ruins of Tróia, above, is in good shape while a 1960’s concrete wall below is so degraded that its rebar supports were already rusting by 2012.

The difference is how we mix our cement that binds the concrete together. This is a story of recipes and chemistry. (Concrete = cement + sand, gravel, rocks.)

- Modern day Portland cement is made by baking limestone and clay minerals at 600oF, then grinding the result and adding gypsum.

- The Romans made cement from slaked lime (quicklime+water), volcanic ash and water.

Scientists discovered in 2017 that volcanic ash + seawater were the secret ingredients that made Roman concrete strong. Those two components were conveniently available in ancient Italy but not economically feasible today. Recently a team of scientists, headed by Admir Masic of MIT, discovered an inexpensive Roman ingredient that helps concrete heal itself.

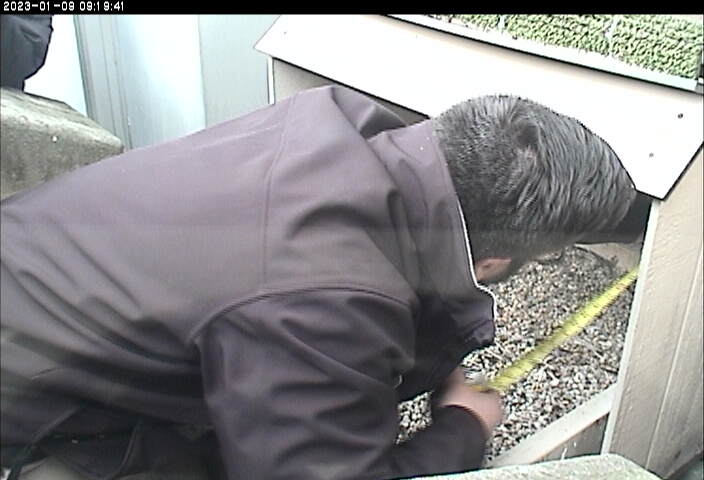

Cement, when exposed to water, can heal very small cracks in concrete by minutely dissolving and recrystallizing. However the cracks must be very tiny in Portland cement-based concrete in order for this to happen — smaller than 0.2 to 0.3 millimeters across (0.0078 to 0.0118 inches).

During the study, the team made Roman-inspired concrete using slaked lime and found that it can heal cracks up to 0.6 millimeters across (0.0236 inches), twice the tolerance of Portland cement.

If our cement used this Roman innovation it would save a lot of damage control.

Find out more in Science Magazine at: Scientists may have found magic ingredient behind ancient Rome’s self-healing concrete

p.s. Slaked lime = quicklime + water. Quicklime is made by baking lime or seashells in a kiln to split the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) into plain calcium oxide (CaO) + CO2. Quicklime is unstable and will spontaneously react with CO2 unless it is slaked with water to set as lime plaster or mortar. — parapharased from Wikipedia