3 December 2022

Gloomy, windy weather has chased us indoors but there’s fun ahead in the coming weeks. Join Audubon’s 123rd annual Christmas Bird Count (CBC), Wednesday 14 December 2022 to Thursday 5 January 2023.

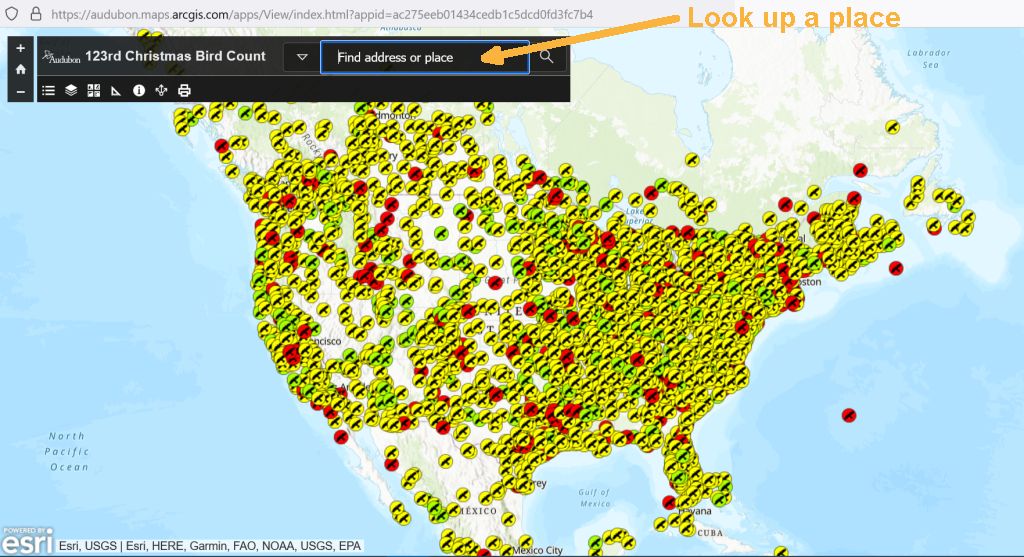

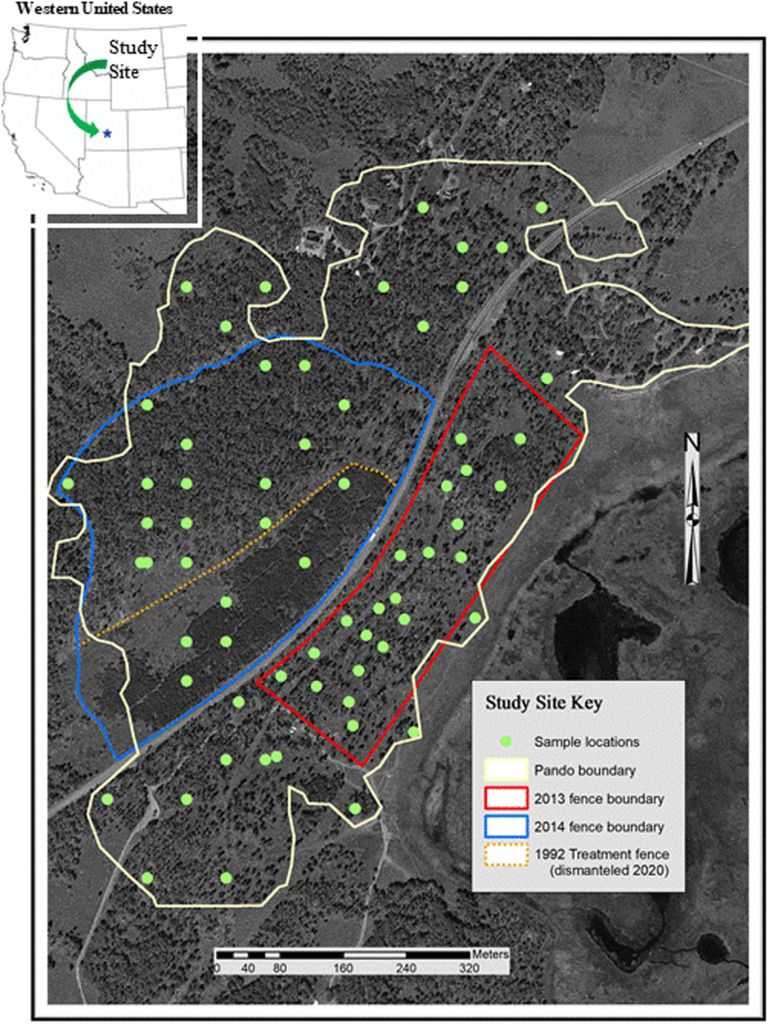

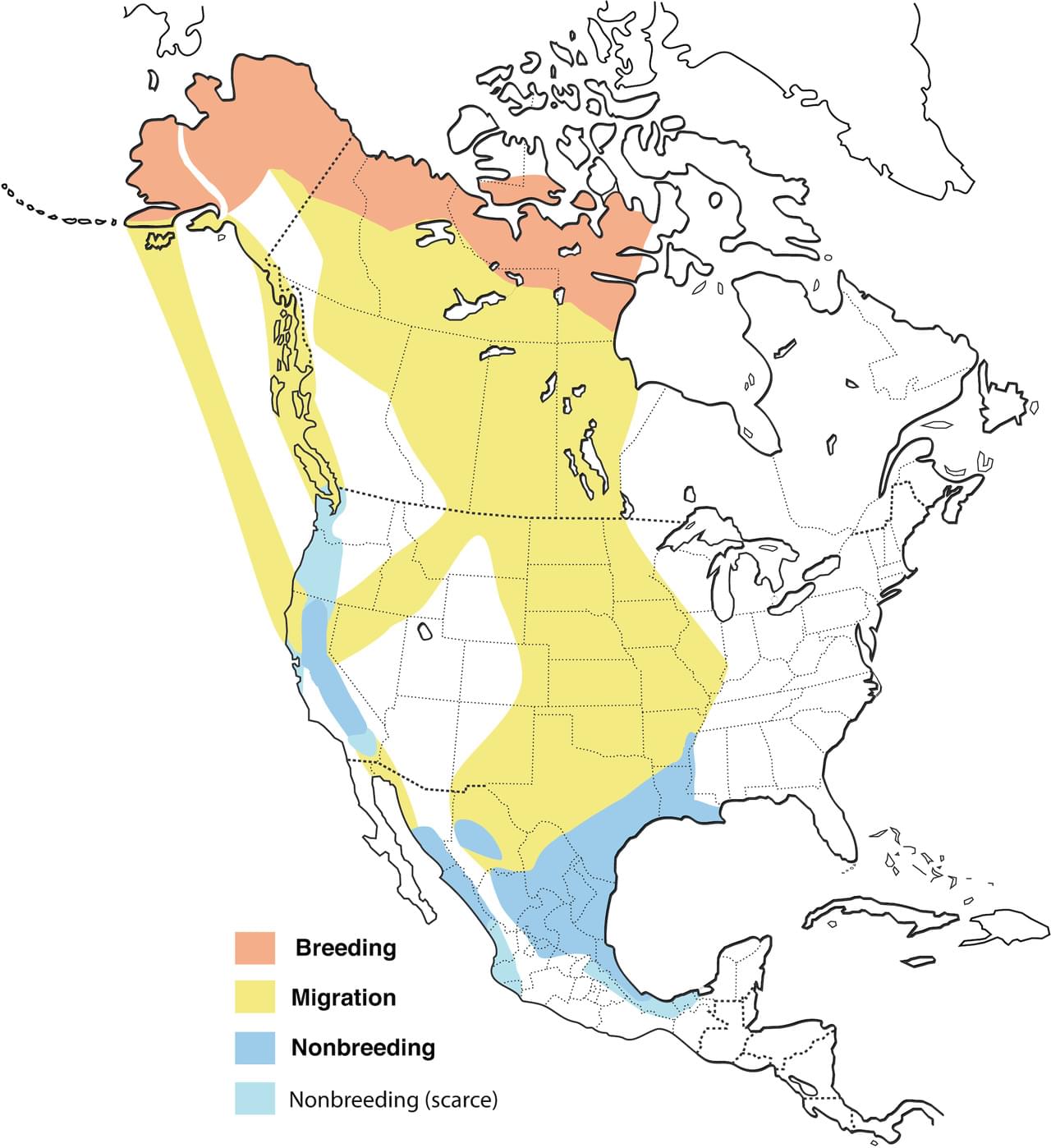

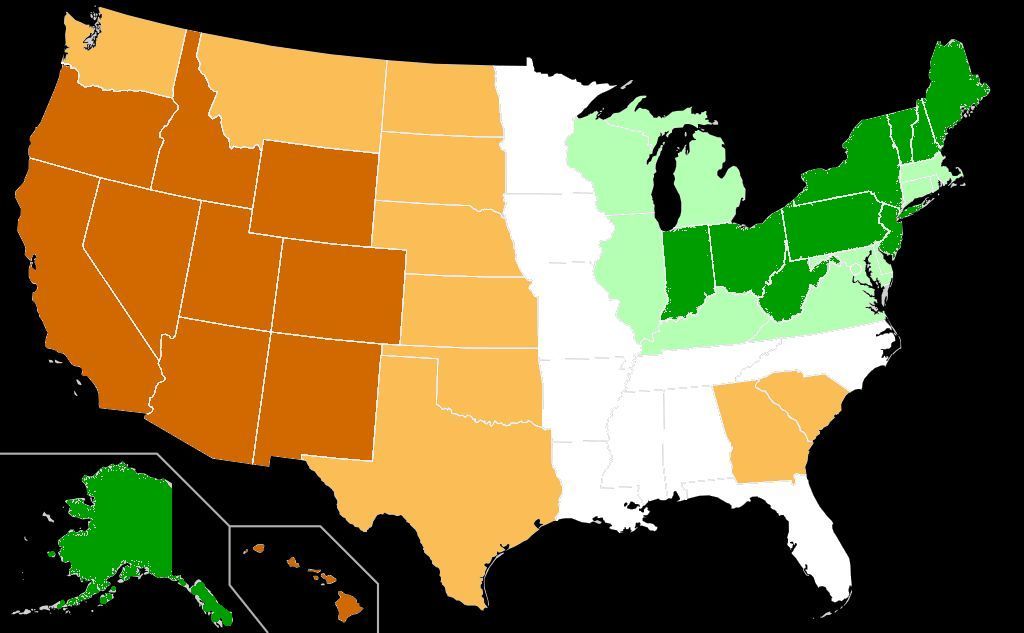

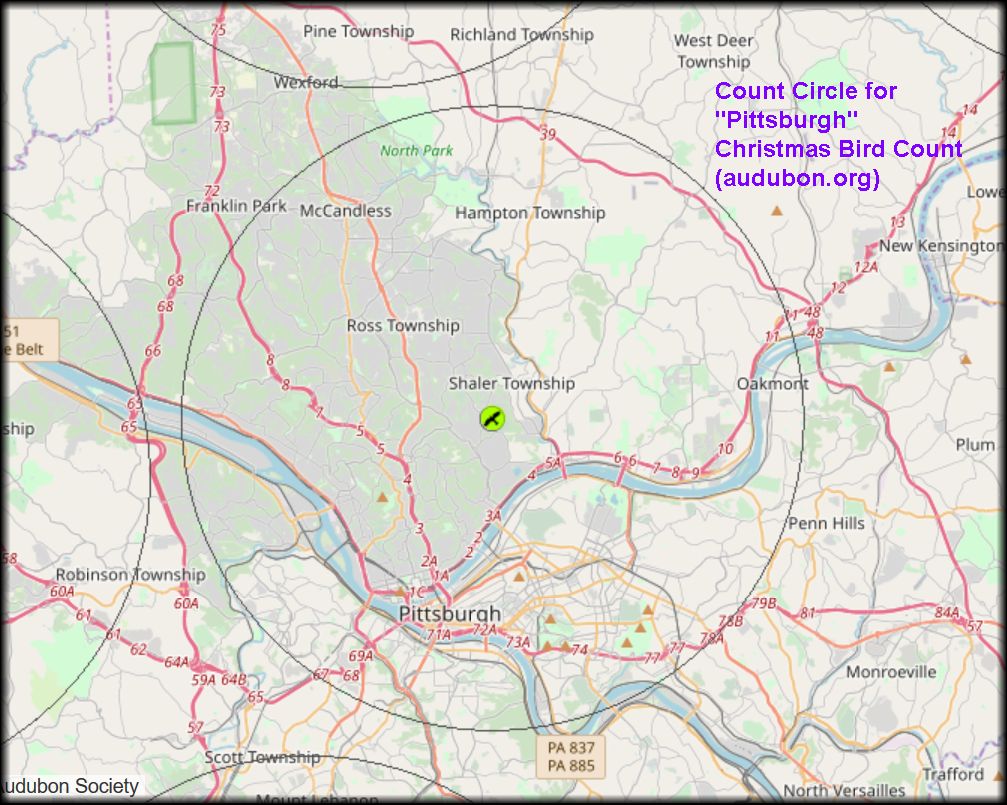

During the Christmas Bird Count, volunteers count birds in more than 2,500 count circles in North America. Each circle is 15-miles in diameter and has its own compiler who coordinates the count for a single scheduled day.

You can go birding outdoors or count birds at your feeder (if your home is in a count circle). No experience is necessary. The only prerequisite is that you must contact the circle compiler in advance to reserve your place.

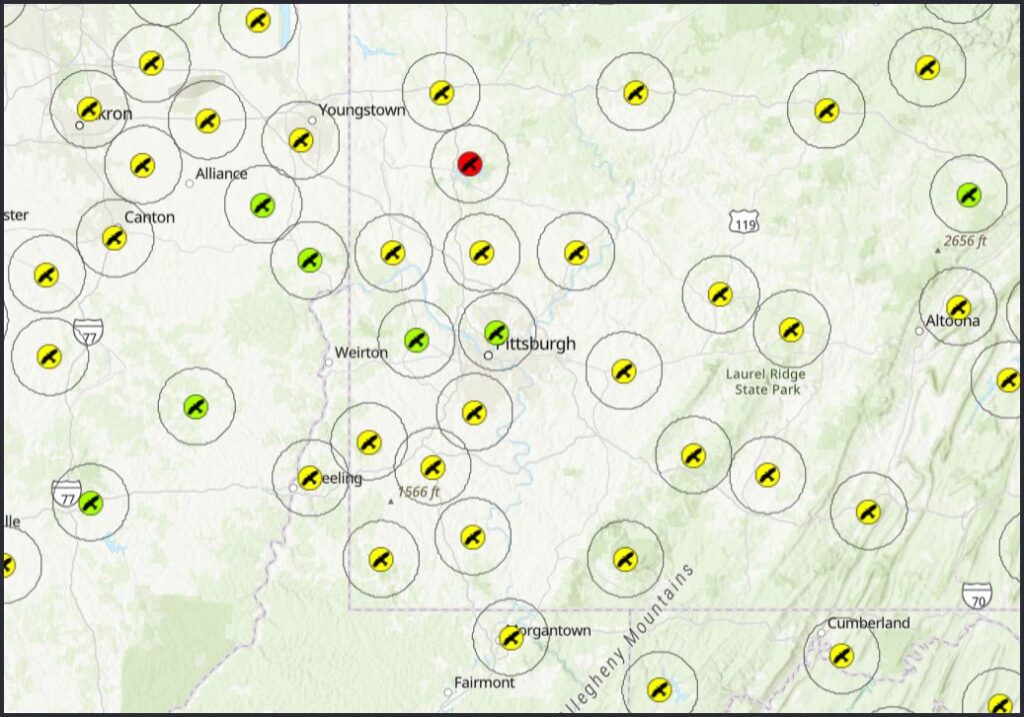

Choose a location and date that suits you from the national map at audubon.org and follow the instructions here for singing up. (NOTE: To see the date of your chosen CBC you may have to scroll down in the little block that shows the compiler’s name.)

If you live in the Pittsburgh area you may be interested in one of these counts. Click on the map for details.

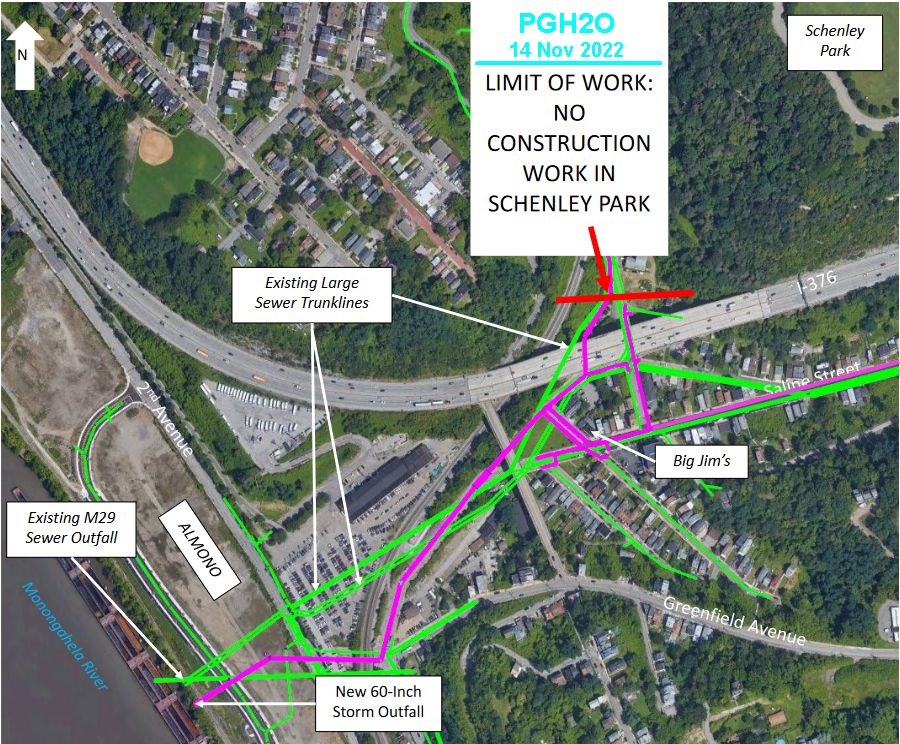

Join the Pittsburgh Christmas Bird Count on 31 December 2022 (map below). If you’ve not yet made arrangements to participate, or you need more information, contact Brian Shema at the Audubon Society of Western PA at 412-963-6100 or bshema@aswp.org.

Sign up now! We’ll be counting soon.

p.s. Did you know … ?

- The Christmas Bird Count is funded entirely by donations. Donate here to support the CBC.

- The CBC extends into January because it spans 11 days before and after Christmas. The entire count period is 23 days, though I doubt any counts are scheduled on Christmas.

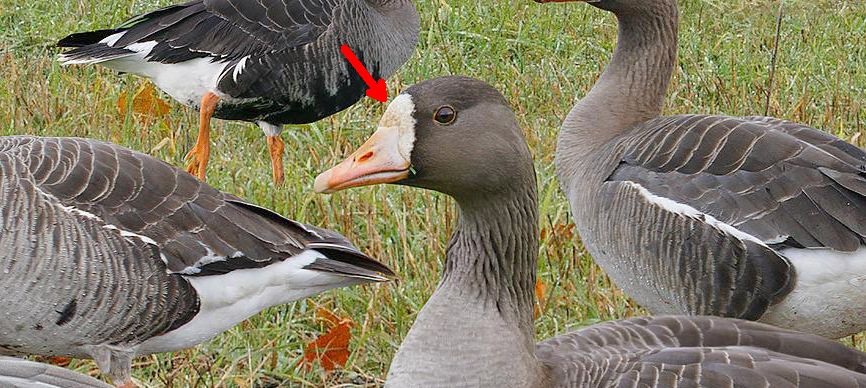

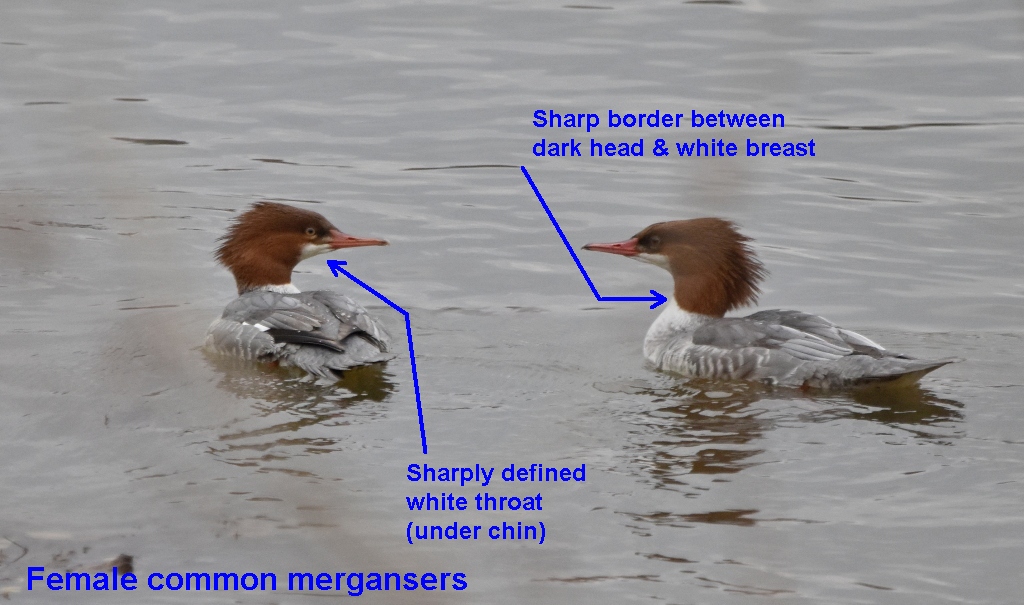

(photo from 2022 Audubon Christmas Bird Count webpage, maps from audubon.org; click on the captions to see the originals)