8 February 2023

In physics the Coriolis force (also called the Coriolis effect) is …

an effect whereby a mass moving in a rotating system experiences a force (the Coriolis force ) acting perpendicular to the direction of motion and to the axis of rotation. On the earth, the effect tends to deflect moving objects to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern and is important in the formation of cyclonic weather systems.

— Definition from Oxford Language via Google Search

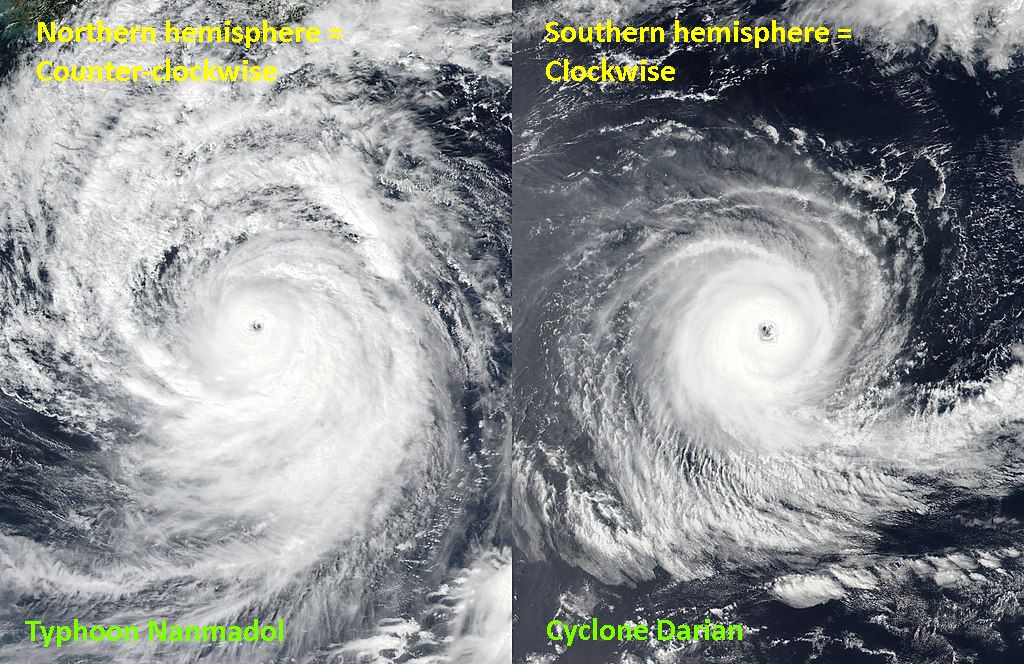

We see this in North American hurricanes, nor’easters and low pressure systems, all of which spin counter clockwise. Because of this, the first winds to hit the Atlantic coast come from the northeast, hence the name nor’easter. Satellite images look like the storm pictured at left below.

Conversely, tropical cyclones in Australia spin clockwise like the one at right. (Cyclone is another name for hurricane.)

I’d heard that the Coriolis force spins water down the drain just like the cyclones so my journey in Ecuador provided an opportunity to find out how water drains at the equator. Does it spin or does it go straight down?

With many opportunities to make on-the-spot observations my results were inconclusive. Sometimes the water spun as it drained. Sometimes it went straight down.

It turns out that the Coriolis force is infinitesimal on draining water. The shape of the basin causes the water to spin! At home in Pittsburgh I have a sink that drains straight down and one that spins clockwise like cyclones in Australia.

Here’s the real story about the Coriolis effect.

Does Coriolis Force affect the drains? No.

(images from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals, video embedded from @SciShow on YouTube)