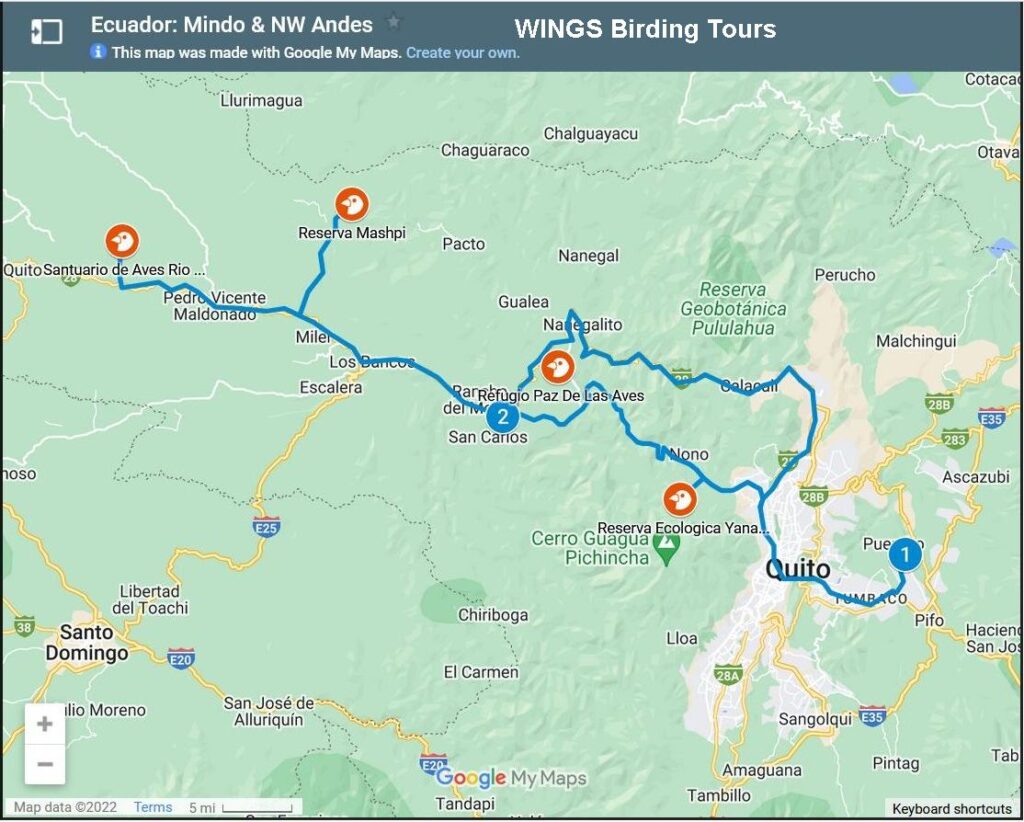

30 Jan 2023, WINGS in Ecuador: Day 2, Yanacocha Reserve on Pichincha Volcano

If you want to see hummingbirds, Ecuador is the place to be. It holds the worlds record for the highest number of species and contains about 40% of the total.

The checklist for our tour has 51 hummingbirds on it, 28 of which have been seen every time WINGS makes the trip. The slideshow displays 20 that we’re certain to see. I tried to memorize them in advance but there are just too many!

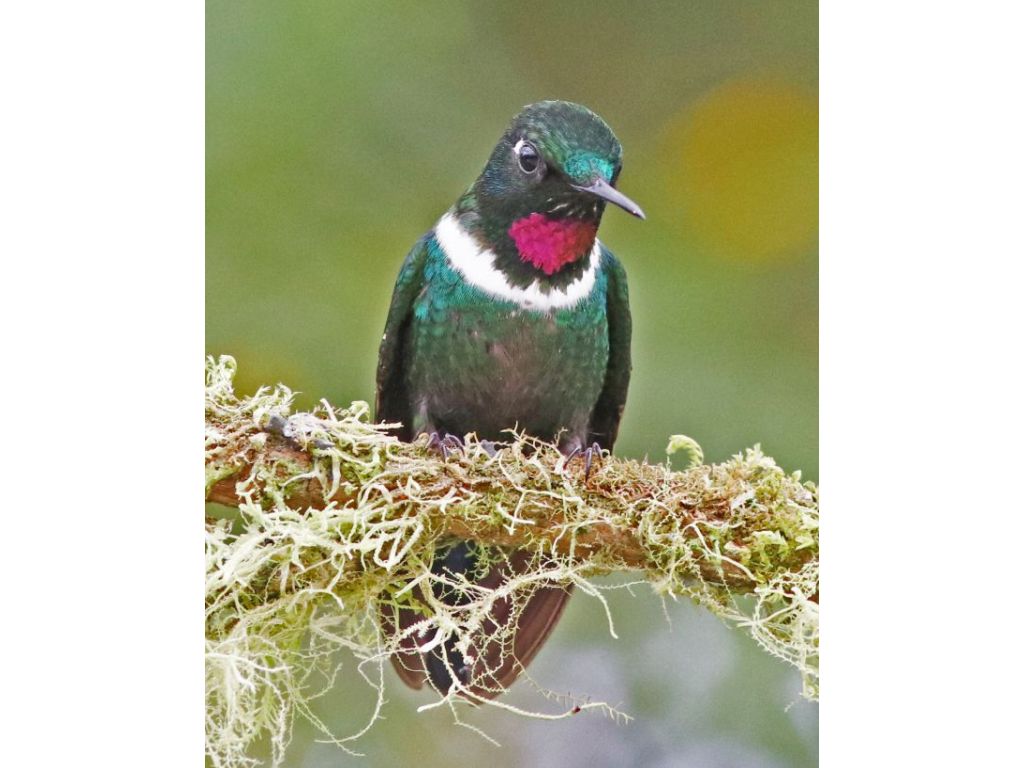

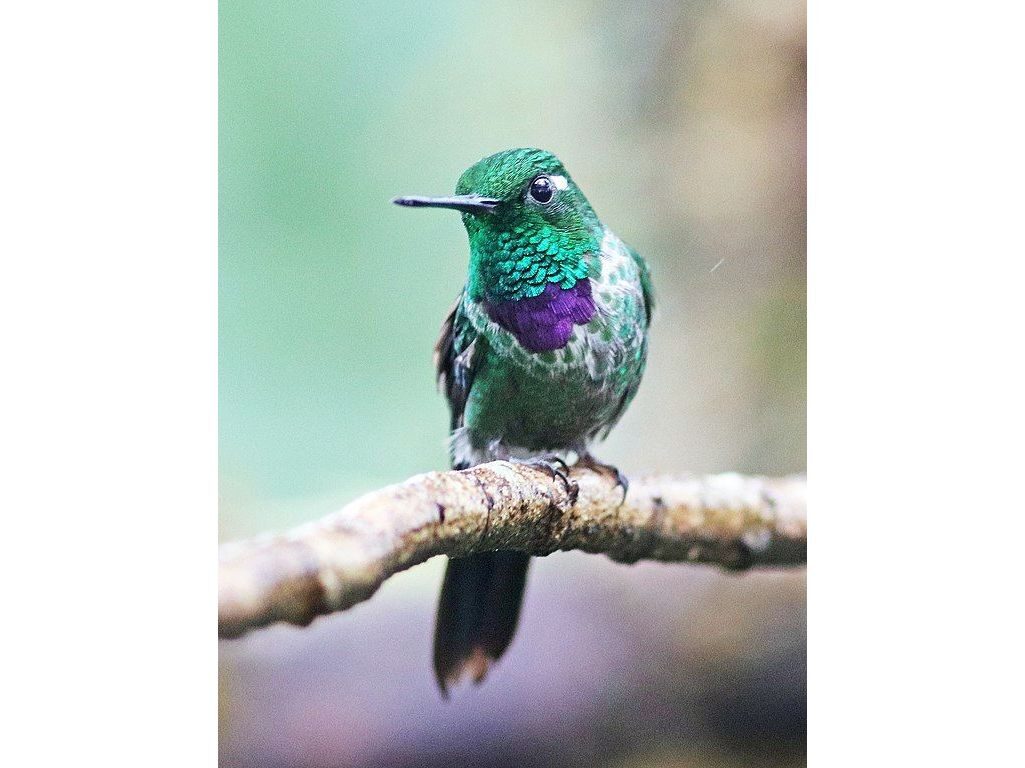

As you look at the hummingbirds, here’s something to watch for: Nearly every species has a white dot, called a post-ocular spot, or a white stripe of feathers behind the eye. Why do they have this and what is it for? My Google searches cannot find an answer.

Here are the species in slideshow order with links to their eBird descriptions and [photo on Wikimedia Commons].

- Andean emerald (Amazilia franciae) [photo]

- Gorgeated sunangel (Heliangelus strophianus) [photo]

- Booted racket-tail (Ocreatus underwoodii) [photo]

- Brown Inca (Coeligena wilsoni) [photo]

- Buff-tailed coronet (Boissonneaua flavescens) [photo]

- Collared Inca (Coeligena torquata) [photo]

- Empress brilliant (Heliodoxa imperatrix) [photo]

- Fawn-breasted brilliant (Heliodoxa rubinoides) [photo]

- Great sapphirewing (Pterophanes cyanopterus) [photo]

- Purple-bibbed whitetip (Urosticte benjamini) [photo]

- Purple-throated woodstar (Calliphlox mitchellii) [photo]

- Sapphire-vented puffleg (Eriocnemis luciani) [photo]

- Sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) [photo]

- Sparkling violetear (Colibri coruscans) [photo]

- Speckled hummingbird (Adelomyia melanogenys) [photo]

- Tawny-bellied hermit (Phaethornis syrmatophorus) [photo]

- Tyrian metaltail (Metallura tyrianthina) [photo]

- Violet-tailed sylph (Aglaiocercus coelestis) [photo]

- Velvet-purple coronet (Boissonneaua jardini) [photo]

- White-whiskered hermit (Phaethornis yaruqui) [photo]

NOTE: The photos may not match exactly to the Mindo Valley hummingbirds because some species vary by location. For instance, see this illustration of the booted racket-tail.

Sigh, wanna see all the booted racket-tails now. https://t.co/9Vc0GrmNqp

— Frank Izaguirre (parroty) (@BirdIzLife) January 11, 2023