6 September 2022

During fall migration bird numbers are at their highest as the adult population is joined by their recent young. I look forward to the variety of fall warblers and large flocks of chimney swifts, but this year — again — there are fewer migrants than I remember. My mood is dampened by solastalgia for birds.

Solastalgia is a new concept developed to give greater meaning and clarity to environmentally induced distress. As opposed to nostalgia–the melancholia or homesickness experienced by individuals when separated from a loved home–solastalgia is the distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment.

— US NIH: Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change

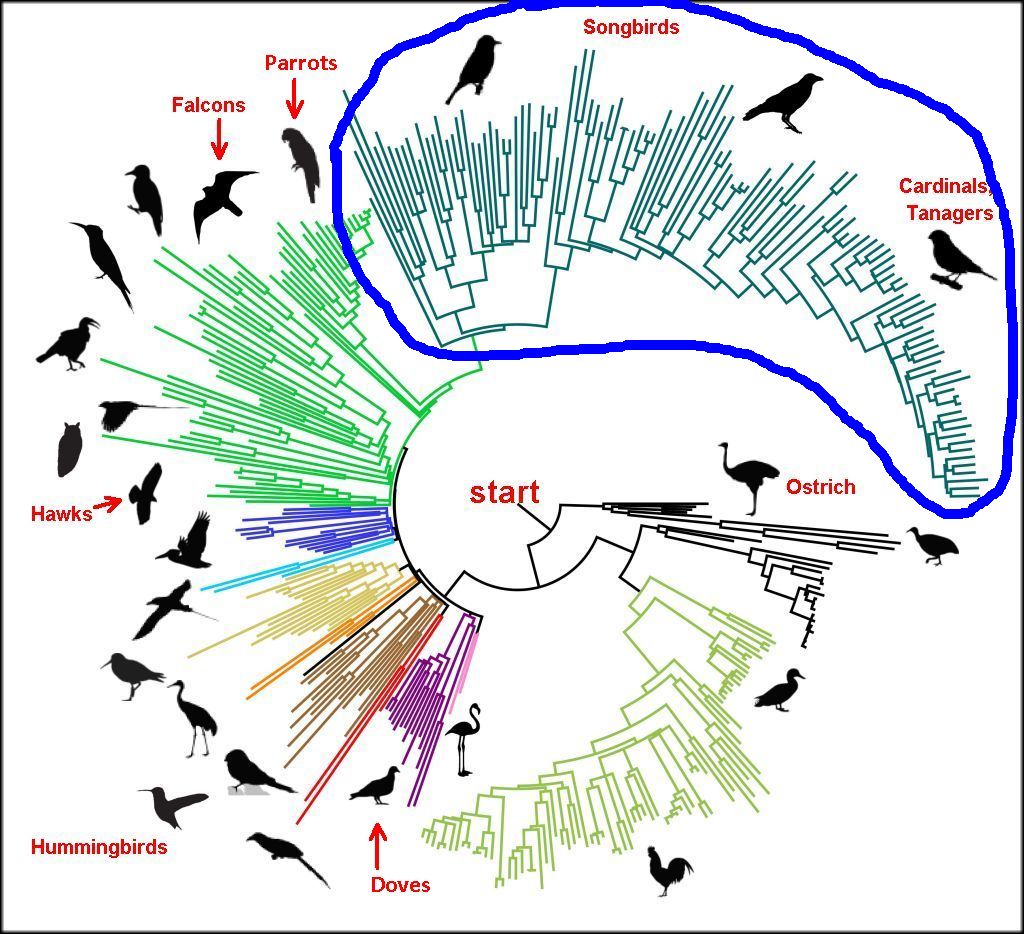

A 2019 bird population study headed by Cornell Lab of Ornithology quantified what I’ve been sensing. In the 50 years since 1970 North America’s total population of birds dropped by 3 billion. However it feels more recent because it has not been gradual. Half of that loss occurred in the past 15 years.

Fourteen years ago I noticed a decline in common nighthawks (Chordeiles minor) that used to migrate in flocks of 10-20 over my old neighborhood during the 20th century. In 2008 their numbers dropped precipitously. Nowadays I am lucky to see a single bird.

Chimney swifts (Chaetura pelagica) were my consolation but now they prompt solastalgia. Two years ago I counted more than 2,200 swifts roosting at Cathedral Mansions chimney during fall migration, but just last year their numbers declined sharply. My highest count in 2021 was only 100. Fifty is my highest count so far this year.

Solastalgia is aptly summed up: “Sometimes you leave a place. Sometimes it leaves you.“

Despite the sense of loss it is still good to be outdoors, it is still lovely to look at birds, and it is healthy to let go of the past and gracefully embrace the present.

For more information on bird decline and some good vibes for the future see 3billionbirds.org.

(see photo captions and links for the credits)