4 September 2022

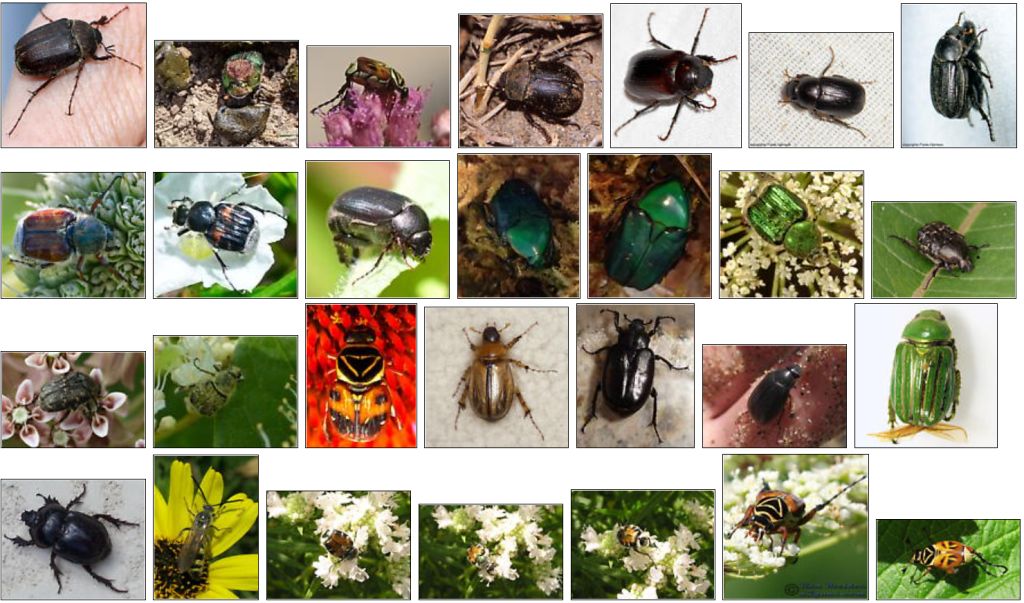

Dung beetles coexist with large animals because their entire life cycle depends on the droppings of cattle, elephants and other mammals. When Scarabaeus beetles find a dung pile each one makes a ball and uses its hind legs to roll the ball away from competitors, then buries it in a private location for later consumption. Here a sacred scarab beetle (Scarabaeus sacer) rolls and digs.

To move a dung ball the Scarabaeus beetle travels backwards in a straight line against all obstacles. When the ball rolls off course, the beetle climbs to the top, reorients itself and resumes pushing in the correct direction. This so impressed the Ancient Egyptians that they venerated the sacred dung beetle (Scarabaeus sacer) and carved amulets in its image(*).

How do these beetles navigate?

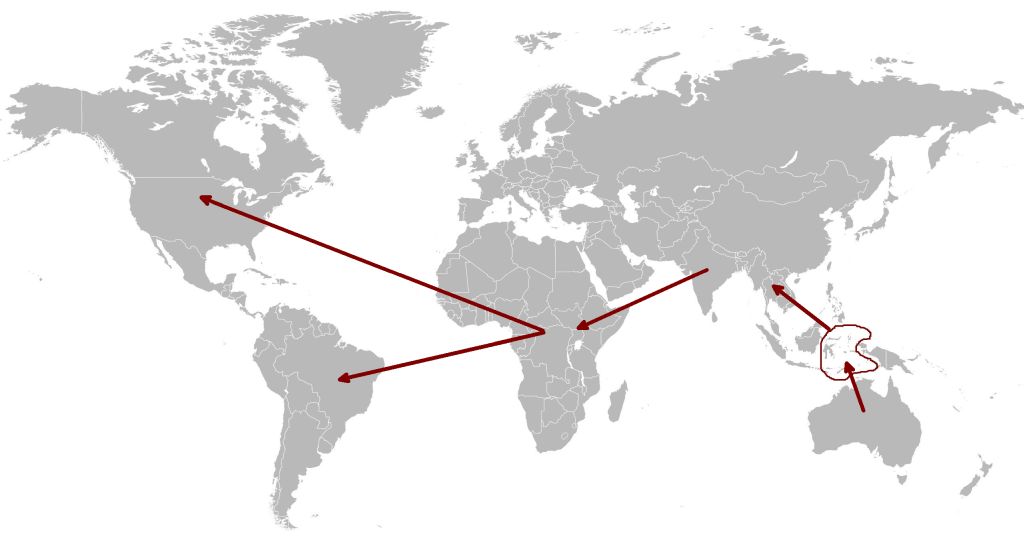

A 2015 study of South African Scarabaeus lamarcki found that the beetles use the sun’s direction and the variation in the sky’s green and ultraviolet colors like a compass. For example, this S. lamarcki beetle travels in the exact opposite direction when researchers use a mirror to show the bug reflected sunlight.

And a 2019 study found that they also pay attention to the wind when the sun is too high to help. See “(Not only) the wind shows the way.”

Traveling upside down and backwards requires lots of navigational tools.

(*)p.s. Did you know that the sacred dung beetle, Scarabaeus sacer, is the origin of scarab jewelry?

The scarab (kheper) beetle was one of the most popular amulets in ancient Egypt because the insect was a symbol of the sun god Re. … The scarab forms food balls out of fresh dung using its back legs to push the oversized spheres along the ground toward its burrow. The Egyptians equated this process with the sun’s daily cycle across the sky, believing that a giant scarab moved the sun from the eastern horizon to the west each day, making the amulet a potent symbol of rebirth.

— MeTropolitan Museum of Art: Egyptian Art, Scarabs

Millennia later, a scarab jewelry pin from the late 1960’s.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and Kate St. John; click on the captions to see the originals)